Carol Bier, Research Associate

Brochure of an exhibition organized by The Textile Museum, Washington, DC, on view 28 March – 7 September 2003.

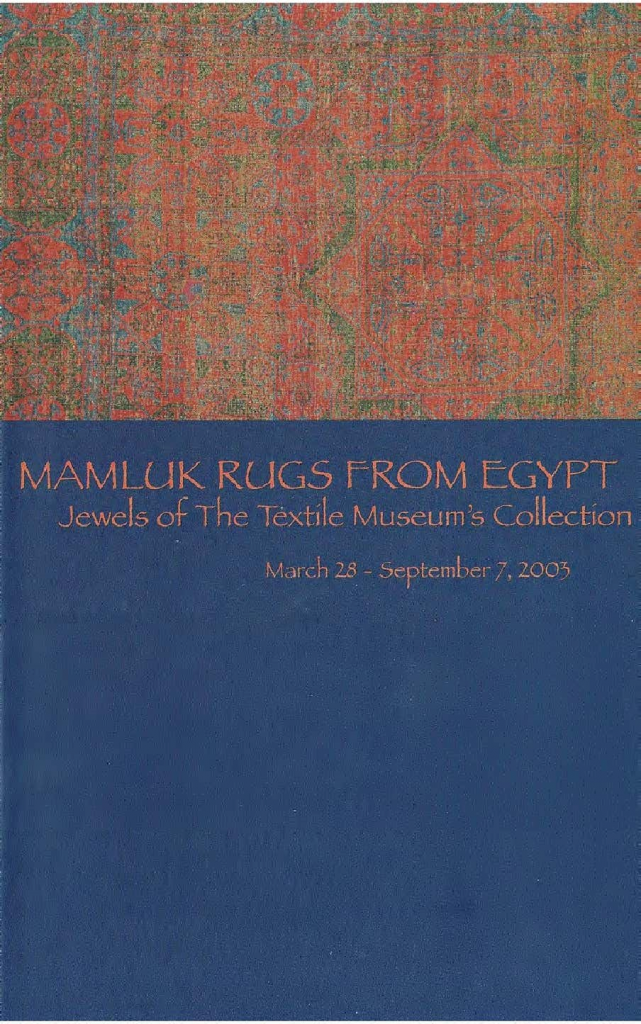

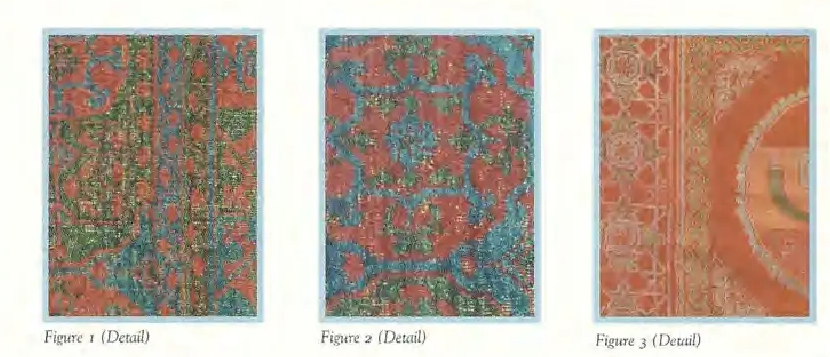

Mamluk rugs are considered by many to be among the most beautiful of any rugs ever created. The brilliant reds, greens, and blues (figs. 1 and 2) are reminiscent of rubies, emeralds and sapphires; whether this was an intentional evocation is not known.

But The Textile Museum’s holdings of Mamluk rugs, unparalleled in the world, are truly the “jewels” of the collection. Simply by virtue of the fact that they date from the late 15th century, Mamluk rugs comprise one of the most significant groups of classical carpets.

Their lustrous wool and wondrous color, as well as their geometric designs and careful execution, contribute to the characteristics of a cohesive group from the points of view of design, structure, materials, color, and layout.

Yet, this is also a group for which many questions remain unanswered. The emergence of this unique group rests upon no known development of rug weaving traditions. Nor is the influence of the three-color geometric patterns of Mamluk rugs felt in later traditions.

In contrast, the weave structure of Mamluk carpets is retained in Cairene carpets manufactured immediately after the Ottoman conquest of Egypt in 1517, which share technical characteristics, while reflecting newly emergent Ottoman floral styles.

Despite such uncertainties of origin and early development, Mamluk rugs show an exceptionally high degree of uniformity, more so perhaps than in any other group of rugs prior to industrialization and mechanized production.

Two rugs in the exhibition (figs. 1 and 2) demonstrate consistency of dimension, color, structure and layout, the proportions of which are determined geometrically.

Larger rugs also show a proportion based on geometry of the circle and the square. Mamluk rugs of the three-color variety (red, blue, green), as well as those with four, five and six colors (the primary three plus white, yellow and brown) also demonstrate similarities of design and layout, as well as consistency in weave structure and yam preparation.

The warps are depressed, which makes identification of the knot formation difficult (symmetrical and asymmetrical knots on depressed warps appear identical on visual analysis without actual penetration of the fabric).

The most frequently encountered knot count is 11H x 11 V, ranging from 100-130 knots/square inch, with a fairly consistent count of 22 warps/inch and 22 wefts/inch. This regularity in knot density in the proportion 1: 1, horizontal to vertical, makes for even-sided polygons such as squares and octagons, as well as circles and right isosceles triangles of uniform dimension.

There are two types of octograms (eight-pointed stars), both of which play with the geometry of the square within a circle. The warps, wool, are composed of four strands, S-spun and Z-plied; most warp sets are dyed green, sometimes arranged in groups forming stripes.

Wefts are often dyed red or pink, and may be two or three shoots. While all of the pile colors usually show a fair amount of wear, areas of brown pile shows extensive loss, which is probably the result of a high iron content in the dyebath, either as mordant or dyestuff.

We do not know where the Egyptian rug-weavers may have obtained the lustrous wool for these carpets; the quality of yhe wool is distinctly different from that Figure 1 Figure 2 Figure 3 which appears in Coptic textiles of an earlier age, or garments from the Fayyum where sheep-rearing has a long history.

We do not know who might have designed the unique geometric repertory of Mamluk rugs, although it is likely that such designs were developed in court ateliers that were also involved in preparation of designs for architectural ornament and the illumination of Qur’ans, for which there are numerous parallels to rug patterns.

Yet, there are also elements in Mamluk rug design that find no ready parallels among the traditions evident in arts of the book, other objects, or architectural decoration. In particular, the umbrella like leaf appears to be unique to rug-weaving, where it is combined in groups of three and five to form clusters, or repeated to form scrolling vines that define both borders and backgrounds.

The red color is also unusual in comparison to other rug-weaving traditions; the dyestuff lac has been proposed, which would presumably have been imported from India.

We do not know why the warps were dyed green, or even where these carpets were actually woven. To judge from the quality of craftsmanship, as well as the consistency of geometric patterns in relation to the monuments created under the patronage of the Mamluk Sultan Qaitbay 0468-96 ), it seems reason able to accept the attribution of these carpets to his reign in the final quarter of the 15th century, and the assumption that they were likely woven in Cairo under supervision by the court.

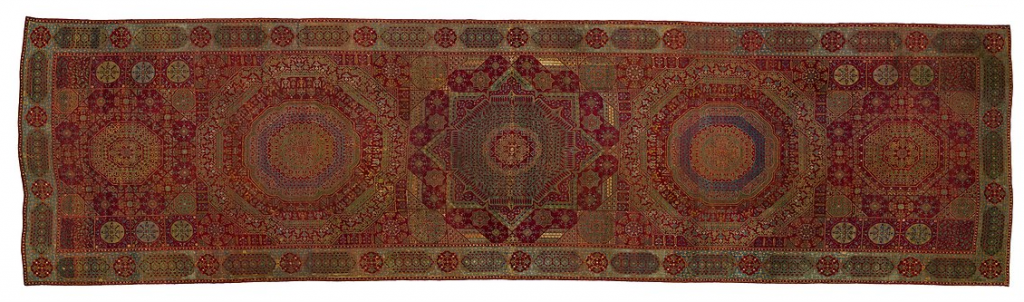

An unusual carpet, known from many fragments in two Florentine museums, and one large fragment at The Textile Museum (fig. 3) contributes further to the complexities associated with understanding Mamluk carpets.

Four of the fragments bear the composite blazon of office of an amir, clearly establishing a link to the court of Qaitbay. Yet the carpet’s technical characteristics, which include its knot count (7H x 7V) and long pile, its colors, as well as its rich repertory of geometric compositions, are distinct from the cohesive design group that we accept as Mamluk by attribution.

With major questions concerning who wove these carpets, under what conditions, and for whose use, this is a clearly an important rug tradition about which much is yet to be learned.

Other signifact Mamluk rugs:

More about Simonetti Mamluk carpet … (click)

A.G.