[From the perspective of collectability, there are] ‘… two [significant] periods in Turkmen history: the era in which most Turkmen practised nomadic pastoralism and were organised according to indigenous structures of affiliation and leadership; and the period following their subjugation by the Russian colonial regime, which is associated with the sedentarisation of nomadic Turkmen and an increasing dependence on the market. (-) Mark Collard

’ The date marking the transition had been established at 1882, the final surrender of the Tekke tribe and the abandonment of Merv, a once thriving metropolis termed by chroniclers as “the mother of the world” .

All pre-1882 Turkoman weavings represent therefore the rarest and most collectible group of artifacts. Conversely, the later 19th and early to mid-20th century works are viewed as mostly decorative.

The period of Turkmen dominance of the Merv Oasis is often referred to as the Classical period, and weavings from that period; classical works.

The common characteristic is the classical Turkmen works can be only established in reference to later pieces which in comparison display busier fields, wider borders, and a finer structure.

‘A predominance of small ornaments in a Turkoman carpet may indicate a later period, as does (…) the ration of the width of the borders to the central field. In classical pieces this proportion is generally between 1:4 and 1:6.’

and ‘… old carpets are significantly more loosely knotted and coarser in structure. As the guls grew smalled and flatter, the knot count incresed and the carpets became ‘finer’.’ (-) Werner Loges Turkoman Tribal Rugs

Therefore, analyses of the technical struture, field ornaments and border motifs in relation to negative space are essential to establish the age and provenance of a given Turkmen textile.

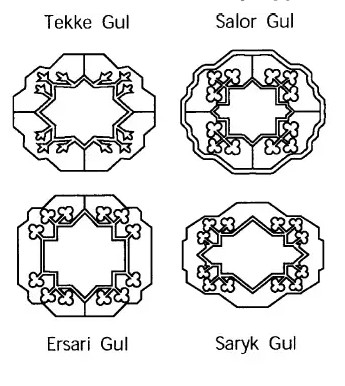

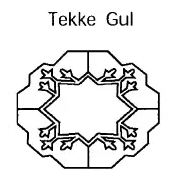

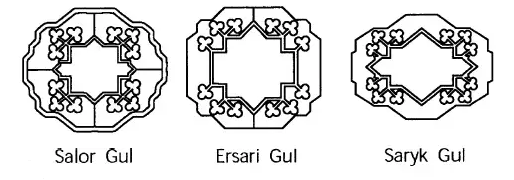

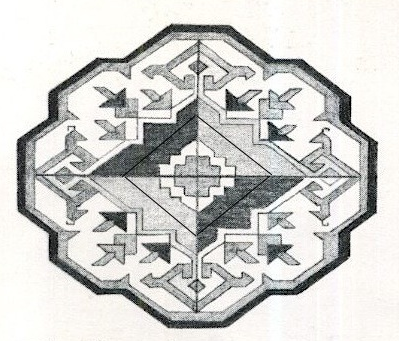

A study of the main carpet ornaments, and the gul in particular, provides evidence of the tribal origin of a given textile.

A gul consists of central ornament and the border; in the field, between the border and central ornament there are projectiles. These appear to ‘darts’ in the Tekke gul (see below),

and ‘clovers’ in in the Salor, Ersari, and Saryk guls (see below).

Furthemore, while the clovers in the Salor gul display a single stem, Ersari and Saryk guls show two.

Prior to the Russian expansion and colonization of Central Asia ‘For centuries the Turkoman people have been bonded together in strongly independent tribal groups. ‘

However, the numerous battles and the final defeat of the Turcoman tribes at Merv (1882) mark the begining of a steady erosion of culture.

The construction of the Trans-Caspian railway encroached on the Turkoman territories forcing many tribes to relocate to Iran and northern Afghanistan.

The Trans-Caspian military railway was inittialy built to facilitate the Russian troops to penetrate Central Asia; armoured trains were a most efficient military means to expand and control newly conquered terrirories. These trains transported troops and later supplies and amunition.

During this period that followed Turkoman women continued to produce various textiles, carpets, chuvals, etc. but not only were those a far cry from the classical period works, they no longer represented, at least not to the same extent, the specific tribal identity.

James Allen, an authority of the subject of Turkman textile arts suggests that ‘The real classical period was before the railroad and when firearms changed to ground rules of their life. The transition period from the bow and arrow horse mounted warrior phase and Turkmen on the run and looking for a place to live their life ‘as well as possible’ was before the Merv Oasis period. This is when the Turkoman weaving arts reached their peak.

The transition, from the production of textiles mainly for domestic use to a more commercial production on a larger scale, Allen argues, was from 1780-1820. This pushes back the prime period of collectable pieces so far that ‘too few pieces exist for the world market’.

A more convenient arbitrary date was established by antiquity merchants to those woven before 1882 (the battle at the Merv Oassis).

At the Merv Oasis, 1847-1882, Turkman rugs were produced in unprecedented quantities and sold to finance the war against Russia.

The Turkmen lost and their traditions started to deteriorate after their defeat. The weaving of the Tekke before 1882 was largely copied from antiques the tribe held; many Merv period pieces have the designs of true classical pieces. They can only by told apart by true schollars (Allen)

This is when the Turkoman weaving arts reached its peak; rugs were produced in unprecedented quantities and sold to finance the war against Russia.

The transition, from the production of textiles solely for domestic use to more commercial production on a large scale, Allen argues, was from 1780-1820 pushing ‘back the prime line of collectable pieces back so far that too few pieces exist for the world market’. A more convenient arbitrary date was established by antiquity merchants to 1882 (the battle at Merv Oassis.)

A.G.