‘It is no great boast, but I believe I was a better hand at worming out a story than either of my fellows (/) …’ (-) Robert Louis Stevenson The Body Snatcher

Ahmad ibn Fadlan, the 10th century Arab explorer spoke of the Byzantine brocaded silks while describing a funeral ceremony of a Volga Viking chief.

For centuries, the Volga served as part of the trade route connecting Scandinavia with the Eastern Roman, and later Byzantine Empires.

There is plenty of evidence to support this thesis; historical records, artefacts: coins, precious metals and gems, textiles.

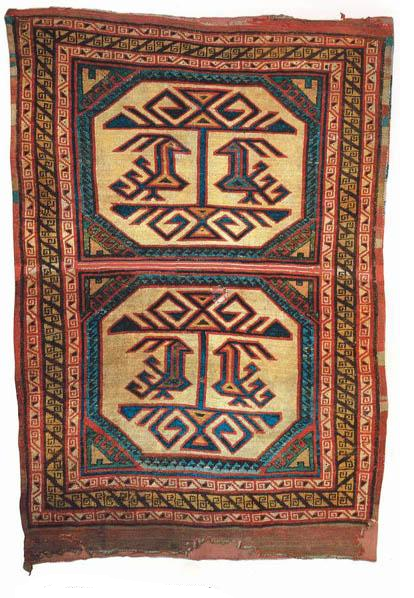

One textile, arguably much later however, attracts more curiosity than those in Viking collections.

It differs from the Persian and Byzantine silks found in burials across Scandinavia, and it closely resembles rugs seen in Italian Renaissance art, namely in works by Domenico di Bartolo and Bartolomeo degli Erri, and perhaps more importantly, in the world-famous Dragon and Phoenix carpet purchased in Rome by Wilhelm von Bode for the Museum of Islamic Art in Berlin.

Since it was found in a parish church of Marby in Sweden, the iconic 15th century artefact has been a subject of intense scholarship.

It is on display at the National Historical Museum in Stockholm as proof of the very early presence of the so-called ‘Anatolian animal carpets’ in the Baltic regions of northern Europe.

The well-known, albeit notorious independent rug scholar Jack Cassin disputes however the Anatolian origins of the Marby rug.

The well-known, albeit notorious independent rug scholar Jack Cassin disputes the Anatolian origins of the Marby rug. ‘[Cassin] had the opportunity to examine (/) several other now famous early ‘Anatolian’ rugs (-) in the London [at] home/gallery of Lisbet Holmes.’ and he argues that ‘the iconography and some of its physical details don’t appear to place the Marby rug within any of the early groups of these animal rugs and surely do not imply and deeper connection to these fragments’ referring to the classification establish and illustrated in Carpet Fragments by Carl Johan Lamm

He also visited Stockholm where he calims to have ‘had the opportunity to see the Marby rug] at very close range’ .

‘[Cassin] had the opportunity to examine this rug when it was with several other now famous early ‘Anatolian’ rugs (-) in the London home/gallery of Lisbet Holmes.’ and he argues that ‘the iconography and some of its physical details don’t appear to place the Marby rug within any of the early groups of these animal rugs and surely do not imply and deeper connection to these fragments’ referring to the classification established and illustrated in the acclaimed Carpet Fragments by Carl Johan Lamm.

What is more, the Marby 1925 discovery constitutes a rather isolated occurrence as there are no mentions of such rugs in Scandinavian church annals, and none has never been found in the Viking burials.

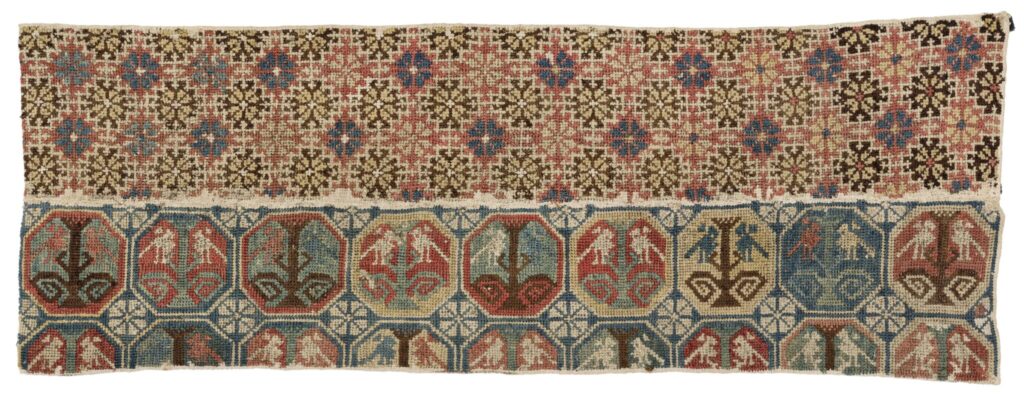

And yet, ironically, there is an abundance of the rug’s principal motif, a tree flanked by two birds, in some of the oldest examples of Scandinavian textiles.

One such textile is a 16th century jynne, a pillowcase from Ramsele Church in northern Sweden. It is now exhibited at the Nordic Museum in Stockholm.

Another, an 18th century jynne, formerly in late Peter Willborg collection, also features the same motif linking it to the rug discovered at Marby.

Marby Church however lies on a pilgrim’s route to Nidaros Cathedral in Norway, and quite possibly, owing to the exuberant costs of the Ottoman rugs in mediaeval Europe, the original location of the Marby rug.

The northernmost Christian cathedral in the world must have been perceived by the Holy Seat as an important place of worship.

The Vatican dignitaries may have visited the site at a point to offer expensive gifts in exchange for future donations, and possibly the exotic Anatolian carpet as well.

If later displayed at the cathedral, the rug may have engendered enough influence in the region to be copied in folk-art across Scandinavia.

In its history, nearly a millennium long, Nidaros Cathedral suffered many calamities. It was ravaged by fires with its entire archives and inventory records gone up in flames.

It was always rebuilt. It also survived the turmoil of the 16th century Reformation.

It is possible that when the newly established Church of Norway took over the Roman Catholic Church ownership of the cathedral, the Anatolian rug, a cherished possession, was sent for safekeeping to Marby.

It may have remained there ever since; left in a crypt of a church in one of the most desolate parts of the country.

Piotr Wesolowski

Additional reading: ANATOLIAN RUG STUDIES: The Marby Rug: Some Questions Examined by Jack Cassin