Polish Carpet Workshop in Isfahan 1943-44

At the outbreak of WWII and following the devastating invasion of Poland by the allied forces of Germany and the Soviet Union; many Polish children, predominantly orphaned, found refuge abroad. The Iranian city of Isfahan stands out in this respect as a place of a particular importance.

Thousands of families expelled from their homes in the Soviet Union-annexed eastern Poland were sent onto a forcible exile in Siberia.

Many died in that harsh and most inhospitable part of northern Asia, but many survived and were eventually allowed to leave.

They were unable to return to their country though, instead, they sought refuge outside of the war-torn Europe.

Thousands reached Iran, mostly children, and found sanctuary in Isfahan.

Children who were evacuated to that ancient Iranian city were welcomed with open arms, at least initially; primary, secondary, and vocational schools were set up to accommodate pupils of all ages.

They were taught metal works, tailoring, and other trades, and a small group of girls of 14-and-over years of age, the art of carpet making.

An experienced Persian instructor supervised learning while an Armenian artist Aleksandr Nerssesyan oversaw the various aspect of the design.

Those young girls never found employment with city’s ateliers; they continued their work at the school which later, perhaps informally, became known as the Polish Workshop in Isfahan.

The project was suddenly interrupted, apparently as a result of increasing hostility toward refugees in the face of famine that plagued Iran in winter of 1943.

‘… the initial warm welcome by the country’s population turned bitter the following winter, when, amid low supplies, Polish refugees were seen as “parasites,” and graffiti (/) read, “all of Persia is hungry as it watches the Poles and the British eat its bread.”’ (Tehran Children Mikhal Dekel)

For reasons of safety, all children were relocated abroad; their journey continued. Many moved to Lebanon, Kenya, New Zealand, and later to Britain. Hundreds of Polish Jewish children were sent to then-British-controlled Palestine.

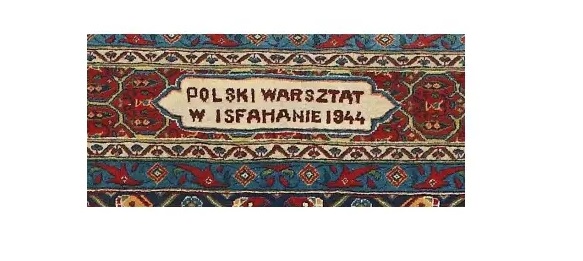

There are four unique Isfahan carpets on a permanent display at the Royal Castle Museum in Warsaw. All four are attributed to the small group of Polish girls from Isfahan. All show an advanced level of skills and save for one are quintessentially Persian in style.

Two exemplify the classic Islamic prayer design. One in an all-over boteh pattern resembles carpets from Sultanabad or Qum; so does the last but it features an image of a white eagle, the Polish national emblem, in the main field. All four bear signatures ‘Polish Workshop in Isfahan.’

The last of the four features the names of the artists: Zofia Cebula, Zofia Wieczorek and sisters Wanda and Jadwiga Igraszek engraved on a brass plaque on its back.

It is believed that two of the four carpets were meant to be gifted to Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt. Both, however, the president of the United States and the Prime Minister of Great Britain were considered to have betrayed the Polish cause at the 1945 Conference of Yalta.

The carpets were sent instead to the headquarters of the Polish government-in- exile at Eaton Place in London.

There was a fifth carpet as well. It was offered to General Wladyslaw Anders, a prominent member of the Polish military elite, ‘our Moses’ as he was referred to by the many survivors of the long journey from gulags of Siberia to Iran and onwards.

Upon his death, the carpet was left in custody at the Polish Institute and Sikorski Museum in London.

There were allegedly a few more carpets, all at one point in London. One was reported lost during renovation works at Eaton Place, others are missing as well.

A note from the author: Despite the support of Władysław Czapski and Irena Godyń , both survivors of the epic journey from the gulags of Siberia to Iran an onwards, the author was unable to establish the destinies of the young talented young girls from The Polish Workshop in Isfahan: the aforementioned Zofia Cebula, Zofia Wieczorek and sisters Wanda and Jadwiga Igraszek as well as Leokadia Kądziołko, Stanisława Leszczyk, Jadwiga Minkler, Marta Pawlus, Leokadia Celińska, Marta Krysińska, Helena Szkuderska, Irena Aulich, Genowefa Czyżyńska, Janina Sowa, and Maria Węgrzyn.

Piotr Wesolowski

Special thanks to Katarzyna Połujan from Pałac Pod Blachą – Muzeum Zamek Królewski w Warszawie