KARABAKH CARPET “GASYMUSHAGY” AND ITS “DRAGON ANCESTORS ”

by

Telman Ibrahimov

Ph.Ds. in Art History Azerbaijan National Academy of Science

The origin of the Karabakh carpets of the South Caucasus have always been distinguished by their artistic and technical properties and ancient symbolism.

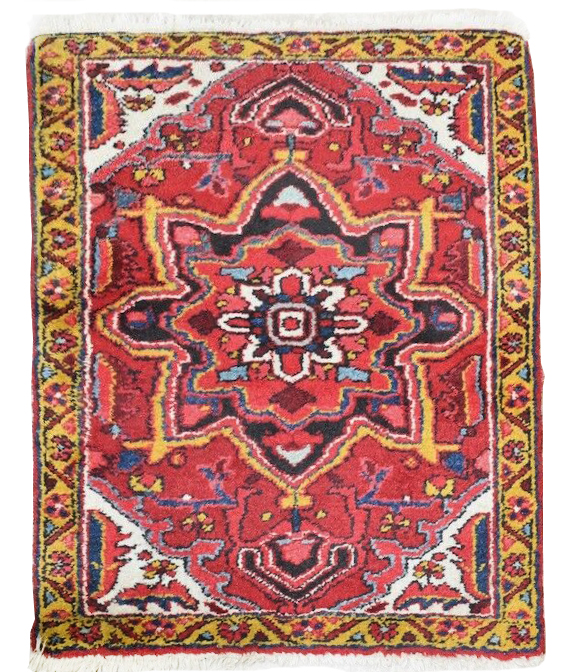

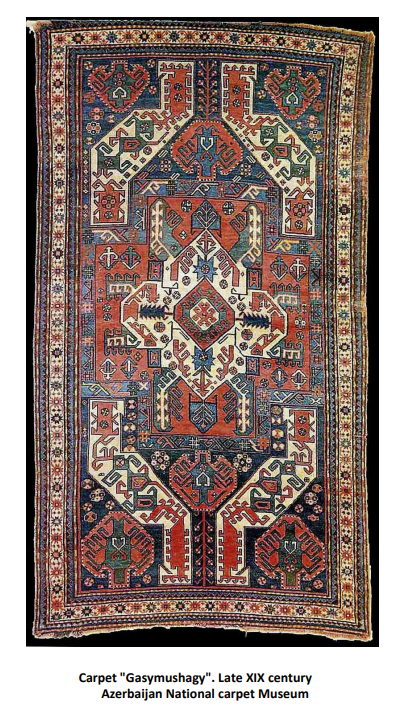

One of the most recognizable in this group is the “Gasymushagy” [Qasim Ushak] carpet.

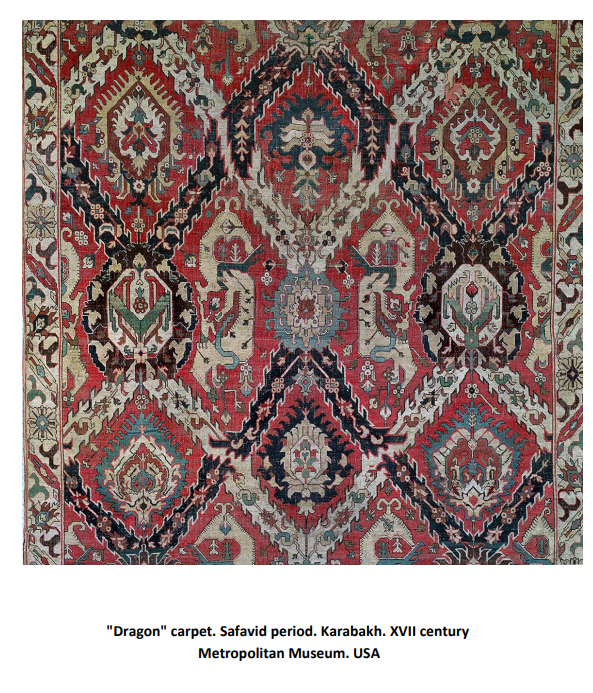

The main design elements of this carpet first appeared in the famous “dragon” carpets of the Safavid era, which allows us to speak about the long-term stability of the traditions of its weaving [Kerimov 1983, p. 221].

Gasymushagy carpets belong to the Jabrail subgroup of the Karabakh group of carpets. The carpets of this subgroup were strongly influenced by the traditions of Tabriz carpet weaving.

This influence was historically due to the fact that the Jebrail region of Karabakh borders (across the Araks River) with South (Iranian) Azerbaijan.

Through Jabrail, the caravan route for centuries connected mountainous and lowland Karabakh with the South Azerbaijan cities of Tabriz, Khoy, Urmia, Ardabil, and others.

In addition to the Jabrail subgroup, the Karabakh group of carpets includes the Shusha subgroup covering the mountainous part of Karabakh and the subgroup of Plain Karabakh with a cultural and craft center in the city of Barda [Muradov 2011, p. 30].

It should be noted that the entire system of decoration of the “Gasymushagy” carpet is formed from various plant and flower motifs, which is a characteristic feature of both Tabriz and Karabakh carpets [Абдуллаева 1971, p. 47].

The rich flora of Karabakh influenced the carpet craft of this region, where stylized motives of local plants, flowers, fruits and berries are easily recognizable.

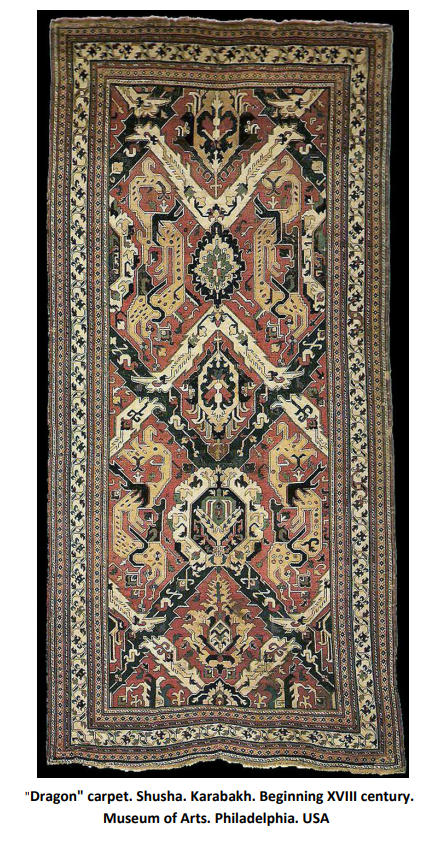

Many experts of oriental carpets, in their classifications, include “Gasymushagy” carpets in the group of so-called “dragon” carpets of Karabakh (in Azerbaijani – “Ajdahaly”)[Maurizio 1996, p. 128]. The common relationship between the “Gasimushagi” carpets and the famous “dragon” carpets of Karabakh is undeniable.

The difference is that dragon carpets have remained an elite product of palace workshops (karkhane) to the end. Whereas, “Gasimushagi” carpets have become widespread in the folk craft of carpet weaving.

Design, symbolism of motives and “artistic ancestors” of the carpet, the emergence and formation of the main motives for the design of “Gasymushagy” carpets fall on the second half of the 18th century – the period of the emergence of independent feudal states in the Caucasian province of the former Safavid Empire.

One of these states was the Karabakh Khanate, which included the Highland and Lowland regions.

The collapse of the Safavid state in the 30s of the 18th century and the formation of independent feudal states on the territory of the Safavid empire changed not only political, but also economic and cultural life in the regions.

The loss of close cultural ties between the Caucasian and Iranian Azerbaijan, as a result of feudal fragmentation, became the reason for the “provincialization” of carpet craft in Karabakh and the emergence of new trends in its development.

At the initial stage, the production of large palace carpets, which were previously made and supplied to the Safavid palaces of Iranian Azerbaijan, sharply decreased.

The number of carpets entering Karabakh along caravan routes from the large carpet markets of Tabriz, Maragha, Ardabil and other cities of Iranian Azerbaijan also decreased.

The severance of trade, economic and cultural ties between Caucasian and Iranian Azerbaijan negatively affected the development of carpet craft not only in Karabakh, but also in other craft centers of Caucasian Azerbaijan

As a result of constant feudal wars that took place between the khanates, internal trade and handicraft ties between Karabakh, Ganja, Kazakh, Arran, Shirvan, Mugan and other regions of the once united Safavid state began to disappear.

Due to the disruption of cultural exchange that fueled the carpet craft traditions, Karabakh weavers had to more and more often modify old carpet designs and create new artistic contexts from old ornamental motifs.

From the end of the 18th century, the old designs of large palace carpets of the Safavid era began to be simplified, acquiring new artistic and technical features. Some of these features formed the basis of new traditions of carpet weaving among the tribes and clans living in Karabakh.

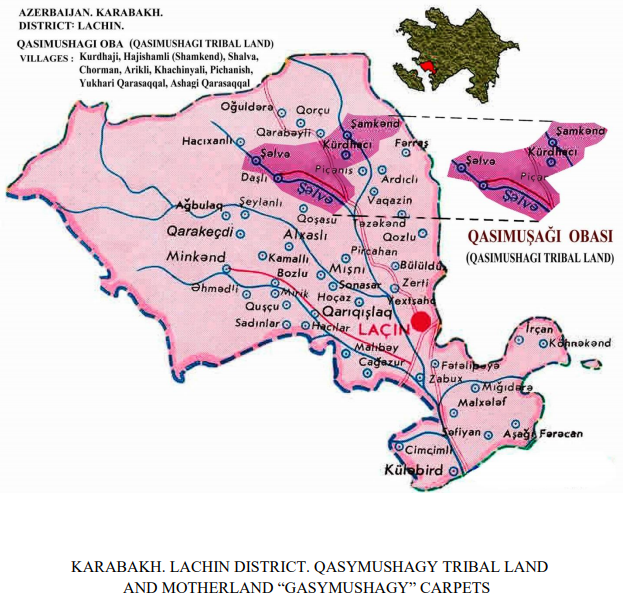

One of these tribes that created their own traditional carpet design was a tribe that called itself – “Gasymushagy”. This tribe historically lived in the mountainous part of Karabakh (modern Lachin region of Karabakh).

The Gasymushagi tribe originated from the Kirkuk Turkmens and considered their ancestor a generic mythical totem (Holy elder), which was called Gasym.

Numerous clans of the tribe called themselves Gasim Ushagy, which meant – Children of Gasym. Hence the name “Gasymushagy” – “Children/Descendants of Gasym” appeared [Ibrahimov 2019, p. 101].

Growing up, the tribe founded new villages, among which were Shamkend, Kurdhadji, Chorman, Shalva, Arikli, Pichenish, etc. Subsequently, all these related villages formed an ethno-territorial area called “Gasymushagy oba” (the area of residence of Gasymushagy [Tribal Land ]).

The ethnic and geographical community of these clans of the same tribe led to the emergence of a common name for the traditional carpets that were woven in the villages of this Tribal Land.

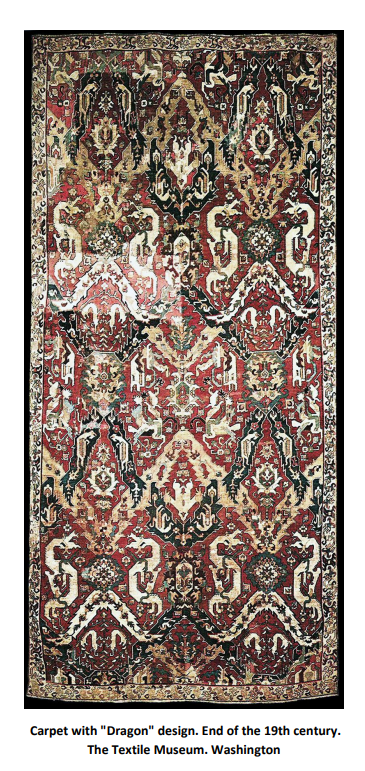

The prototype of the main motive of the “Gasymushagy” carpet was already present in the old “dragon” carpets of Karabakh, woven back in the Safavid era.

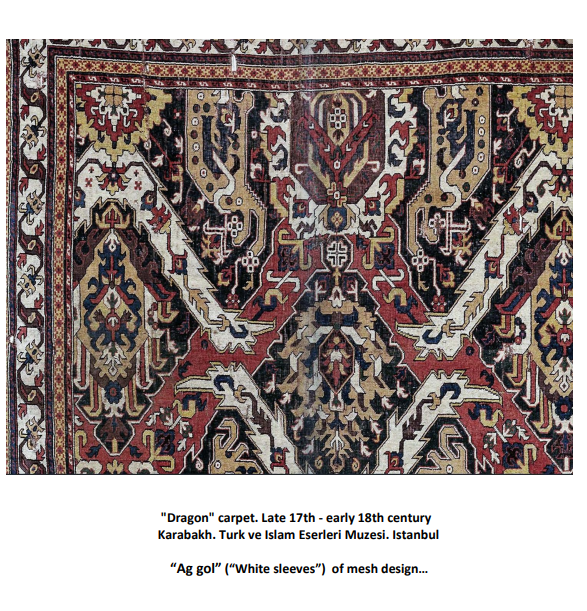

In those carpets, the prototype of the main motif of the Gasymushagy carpet – Ag gol (“white sleeve”) was present as one of the mesh design elements.

The prototypes of the “white sleeve” motif in those carpets have an easily recognizable plant-floral content.

In their design, contrasting white and black leaves contribute to the overall lattice structure of the middle carpet field. The diamond-shaped cells of the lattice usually contained images of dragons, which gave the name to these carpets.

The lattice formed from white and black leaves symbolized a “magic protective net” and, in fact, was a talisman. The symbolism of this “magic net” postulated the image of a mystical, impenetrable and enchanted forest, in which the dragon protectors live forever.

The “white sleeve” motif in Gasymushagy carpets is a stylized imitation of the white jagged leaves that we saw in old “dragon” carpets.

The design of old Safavid carpets is known in Azerbaijan under another, old name – “Khatai”. Since the second half of the 18th century, first in the embroiderys and later in the carpets in the local Gasymushagy carpets, the complex old design of the Safavid “dragon” carpets has been fragmented.

The reason for this is that at this time, orders for the creation of large and luxurious carpets to decorate the Safavid palaces ceased to come.

Reducing the size of the carpet and simplifying the design was carried out by the fragmentation of the design of the Safavid carpets. Not the whole carpet was woven, but one or two of its fragments.

The simple limitation of the woven piece with a decorative border gave the new carpet a complete and solid look. Thus, the intricate mesh designs of the Safavid “dragon” carpets gradually turned into medallion designs.

The disintegration of the centralized Safavid state and the transformation of its former Karabakh province into an independent feudal state led to the fact that representatives of the middle class became the customers of carpets.

In the Safavid era, the main customers for carpets were representatives of the palace aristocracy. The change of customers influenced not only the size of the carpets, but also the richness of the decor and the quality of the materials.

At the same time, one should not forget that the technical designs of carpets were now created not by professional palace artists, as before, but by local craftsmen and weavers. All this could not but affect the artistic and technical quality of the carpets.

The early stage of creation and formation of a new design of the “Gasymushagy” carpet is most clearly reflected in the folk embroidery created in “Tribal Land Gasymushagy”.

In the earliest examples of these embroideries, the “Ag gol” (“White Sleeve”) motif known to us, as in the “dragon” carpets of the Safavid period, is still an element of the mesh design. At the same time, already in these embroideries the motif of the Safavid “dragon” is replaced with a flower medallion.

As a result of this “restyling”, the old design of “dragon carpets” acquired a new artistic interpretation – first in folk embroidery, and then in local carpets.

These Karabakh embroideries adorn the expositions of many museums today [Boralevi, Samadova 2017, p. 40]. The central medallion of the “Gasymushagy” carpet, together with the adjoining “Ag gol” (“white sleeve”) motifs, forms the main distinctive motive of the carpet.

The design of the medallion has a floral origin, however, the old weavers called it “Azhdaha” (“Dragon”) and “Agrab” (“Spider”) [Абдуллаева 1971, p. 47]. The motif of the central medallion, which “migrated” from embroidery to carpets, has acquired a more geometrized and stylized form in the form of a large four-petal rosette.

Along with the central medallion and “white sleeves” (“Ag gol”), the design of the carpet also contains small ornamental motifs that fill the space of the central field.

Most of these motives are of a vegetable nature and depict flowers, buds, leaves, bindweed.

There are also geometric, astral, zoomorphic, anthropomorphic motives and tamga (tribal) signs. In the middle field of the carpet, you can often see hook-shaped talismans and images of the mother goddess [Kerimov 1985, p. 14].

As noted above, the “Gasymushagy” or “Ag gol” carpet has several border options. The main (wide) border has two options: in the first, we see stylized and geometrized zoomorphic motifs. The design of the second version consists of repeating motifs “khyrda g ü l” (small, wild flower).

Variants and modifications of the main motive “Ag gol” (“white sleeve”) of the “Gasymushagy” carpet are found in other carpets of the Karabakh group as well as in carpets from neighboring regions of Azerbaijan.

In Karabakh carpets, this motif can be seen in the “Chelebi” and “Bakhmanli” carpets. A slightly modified and reduced version of the “Ag gol” motif is available in the designs of the Guba carpets “Alpan”, “Zeykhur”, “Gollu Chichi” and others. The design of the “Ag gol” (“Gasymushagy”) carpet was finally formed in Karabakh by the end of the 19th century [Исаев 1932, p. 127].

By this time, the tendency to schematize and stylize the design of the carpet even more intensifies. One of the main reasons for this was the decrease in the density of knots in carpets of the late 18th – early 19th centuries.

Thick and coarse threads did not allow adequate repetition of small and complex motifs of old Safavid carpets. Having undergone “restyling”, the design of the Karabakh carpet “Ag gol” (“Gasymushagy”) has completely changed.

First, this happened in flat-woven sumakh carpets and only then in pile carpets. The next stage of further simplification of the design of “Gasimushagi” carpets falls on the 19th century.

At the end of the 20s of this century, the historical territories of the Azerbaijani people were divided between Russia and Iran. The territories located north of the Araks River, including Karabakh, became part of the Russian Empire, and the lands south of the river were annexed to Iran.

This historic event led to the final severing of historical and cultural ties that unite the Karabakh and Tabriz carpet traditions.

The economic policy pursued by the Russian Empire in the territories of its colonies also influenced the carpet art. Thus, at the end of the 19th century, the Caucasian branch of the All-Russian Handicraft Committee undertook large-scale measures to increase the production of carpets in the South Caucasus.

The increase in the circulation of carpet products, their commercialization – led to an even greater simplification and standardization of Karabakh carpets, including the “Gasymushagy” carpet.

Commercial popularization and dissemination of carpet craft in Karabakh already in the Soviet era (after 1920) had both positive and negative results.

The positive thing is that the ancient traditional craft of carpet weaving in Karabakh received a new, strong impetus for development.

The negative result was the commercial simplification of designs, reduction in size and reduction in the quality of carpet materials.

All this taken together contributed to the fact that traditional Karabakh carpets turned from unique works of art – into a handicraft consumer goods for citizens with limited financial resources.

Conclusion

The Karabakh carpet “Gasymushagy” with an unusual design has come a long way of development – from large “dragon” carpets of the Safavid era – to small medallion carpets with white paired “sleeves” (“Ag gol”) extending up and down from the central medallion.

The carpet, created in a small ethno-geographical region of Karabakh, called Gasimushagi oba (Tribal Land – the habitat of the Gasimushagi tribe), was created and woven in the context of artistic and technical traditions that unite the carpet crafts of Tabriz and Karabakh.

The Gasymushagy carpet, the traditional design of which was finally formed at the beginning of the 19th century, possessing all the features characteristic of Karabakh carpet weaving, nevertheless, has many parallels in the motives and symbolism of the neighboring carpet weaving centers of Azerbaijan.

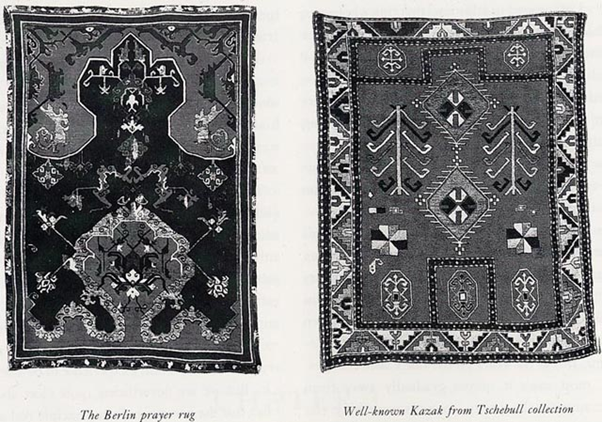

These are the parallels. and sometimes a clear kinship is observed in the carpets of Shirvan, Nakhchyvan, Kazakh, Kuba and even neighboring Dagestan.

References

1. Абдуллаева Н. Ковровое искусство Азербайджана. «Элм». Баку 1971. Стр.42,47.

2. Boralevi Alberto, Samadova Asli . Exibition Curators. Azerbaijan Embroideries from the 16th -18th centuries. The 5th International Symposium on Azerbaijani carpets. “Silk Treasures”. Exibition Catalogue. Baku 2017. P-s. 36-45

3. İbrahimov T. Qarabağın “Qasımuşağı” xalçaları. Научно-публицистический журнал “Azərbaycan xalçaları”.№28/29. 2019

4. Исаев М.Д. Ковровое производство Закавказья. Тифлис. 1932. Стр.125-129

5. Керимов Л. Азербайджанский ковер. Том III. “Гянджлик». Баку.1983. Стр.221-223

6. Kerimov L. Azerbaijan Carpet. “ Jazichy” Baku 1985. Стр.14

7. Maurizio Cohen. The World of Carpets. “Crescent Books” New York 1996. P. 128

8. Muradov V. Azərbaycan xalçaları. Qarabağ qrupu. “Elm”. Bakı 2011. Стр.30-31

9. Gasimushaghi carpets. https://www.essgocarpets.com/blog/gasimushaghi-carpets/

10.Azerbaijani carpets from the Museum of Turkish and Islamic collection. Istanbul 2019