Tribal rugs from Iran’s Zagros Mountains have for decades captivated the attention of rug collectors the world over.

At auctions, the tribal works by the Qashqai, Bahtiari and Afshars would at times outsold exquisite artifacts from the most prestigious palace workshops.

The charm of these primitive works of art in textile rests mainly in their fascinating play of colours, and their spontaneity of design.

Among these tribal wonders, a coarsely woven, long-pile and low-knot density gabbeh plays a very important role.

Efforts by rug collectors and educators such as Jim Opie and late Peter Wilborg led to increased popularity of gabbehs (Bahtiari Kersaks) bringing this ancient ‘uncomplicated’ art out of the ‘black tents’ to the world museums, and the market at large.

‘The increased interest in gabbas among Western collectors since the 1980s and a shared aesthetic with minimalism and the color field movement in modern art, as well as a contemporary appreciation of the charm of gabba rugs, have led to higher demand [and] has spawned commercial manufacture …’ (Jean-Pierre Digard and Carol Bier)

The first references to gabbeh can be traced in texts dating to the middle of the 16th century (J. Opie), however:

‘Some authors believe that gabba represent much older traditions of pile weaving, and that their origins may date to the emergence of this technique in the steppes of Central Asia soon after domestication of sheep.’

(J-P. Digard and C. Bier)

This thesis is strongly argued against by J. Opie:

‘… [there is] abundant evidence of extremely old tribal design traditions in western Asia, especially in Iran, [suggesting that e.g.] Luri gabbehs, like indigenous Luri weavings did not merely survive in southwest Iran, but originated there, and that the weaving techniques involved were even more deeply rooted in western Asia than they were, out on the steppes.’

Sadly however,

‘Those that have survived date only from the last two centuries. There is evidence, however, that the lion motif was utilized by rug weavers prior to this.’ (Tanavoli)

These gabbehs, insinsts Opie, originated in Luristan taking root later further north among the Kurdish tribes as far as Sanandaj, Nehavand, Bijar and south among the Qashqai (also Tanavoli, Amanolahi)

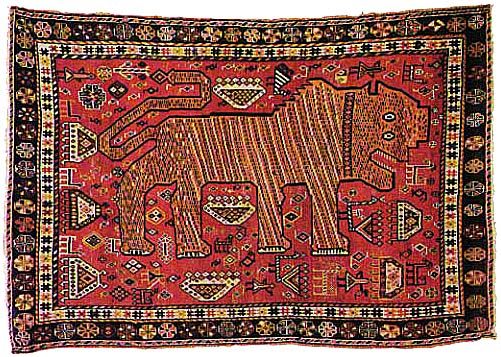

An interesting element common to gabbeh are the various representations of anthropo- and zoomorphic motifs. A gabbeh that stand out in this respect is the so-called gabbeh-ye siri, the lion gabbeh.

The technical structure of the lion gabbehs – a higher knot-count, lower pile – may suggest their greater relevance among the nomads alluding perhaps to some very distant shamanic past.

‘Lion guards the tent’ (Opie); a tent represents a family.

Lions represented in the earliest style of gabbeh-ye siri, do not however feature a lion as we know it. The African lion, it is believed, begins to appear in much later works. It was introduced to Iran through images on imported objects during the Kajar period.

Lions featured in the pre-Kajar gabbehs (circulating in much later replicas and only known to us as such) are representations of a mythical creature symbolizing majesty and masculine power rather than a long extinct Asiatic lion as it is often suggested.

Bazaars in Iran are inundated with commercial replicas of lion gabbeh; they are extremely popular with visitors from abroad.

This is in part at least owed to the extraordinary success of the Iranian artist and avid rug collector Parvez Tanavoli, who views those ‘primitive’ works as a genuine expression of artistic traditions rooted in mankind’s long-forgotten mythologies.

Tanavoli,’s art remains profoundly inspired by the gabbeh imagery, colour and obscure symbolism.

Tanavoli,’s art gained the artist his world-fame and recognition while bringing the spotlight onto that very ancient and genuine artform.

A.G.

Read more about Pavez Tanavoli in our next newsletter