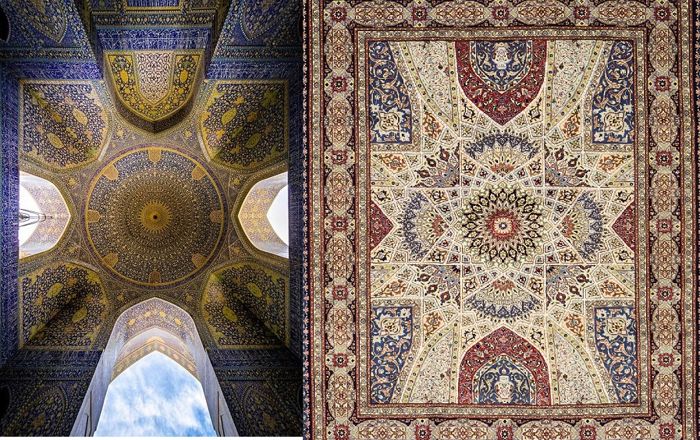

‘Just as when we step into a mosque and its high open dome leads our minds up , up , to greater things , so a great carpet seeks to do the same under the feet …’ – Anita Amirrezvani The Blood of Flowers

It is believed that Art has its roots in the mystic experience, and if rugs are to be viewed as works of art, which no doubts they are, the origins of their symbolism ought to be sought in religion.

The Islamic carpet traditions abound in examples of the religious influence; carpets from Ishahan and Tabriz often reflect the mosaic vaults in the city’s mosques. It is an aesthetic accent that developed in Islamic arts when the first carpets were brought into the mosques.

There is a philosophical dimension to this: the sacred space in the centre of the mosque is to reflect the heavenly order above and carpets in such mosques as, for instance, the contemporary Sheih Zayed Gran Mosque in Abu Dhabi are placed directly beneath the vault.

The enormous hand-made Persian carpet’s medallion reflects the intricate gold and crystal chandelier extending to the vault above in Shaih al Zayed Grand Mosque, Abu Dhabi

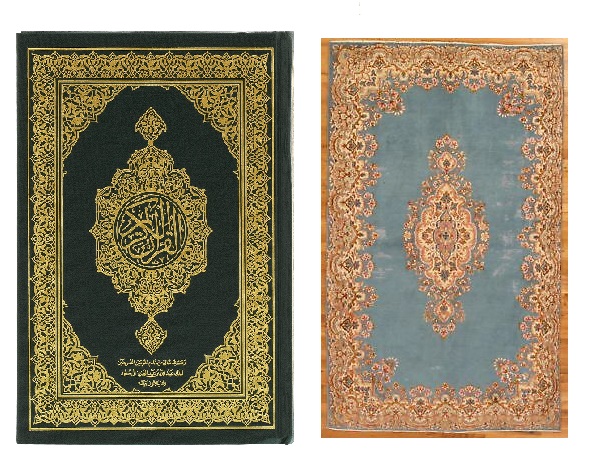

Carpet artists from the Persian city of Kerman created a unique pattern referred to by merchants, collectors and scholars alike as the Koranic design. The Koranic design reflects the great Islamic book bidding tradition and resembles the very common cover of the revered Quran.

Elaborate prayer rugs designs evolved also from the mosque settings appearing initially as permanent patterns stencilled in the rows facing al Kibla and designated for the devotees during the prayer.

Since prayer is compulsory in Islam, and regulated by the movement of the Sun, but not limited to a mosque; travelling Muslims found themselves often praying en route, more often than not, far from the comfort of the sacred spaces A portable prayer rug became indispensable to early caravanners, and other travelling followers of the Mahometan religion.

The evolution of the so-called ‘prayer design’ extends however beyond the rug’s functionality; prayers rugs, particularly that from the Ottoman period became a means for the expression of the spiritual devotion. The most intricate work of Islamic woven arts in silk and silver or gold brocade such as those from Hereke have never meant to be prayed on but looked at instead in awe and contemplation of the Almighty, Allah.

As it often happens, art transcends religions; there are rugs where Islamic symbols appear next to Christian crosses as it is the case with the Anatolian and Beluch prayer rugs (see below)

Tribal rugs from Anatolia, the Caucasus, various parts of Iran and other parts of the Orient show sacred motifs shrouded the mist of long forgotten mythologies. It takes in fact a scholarly effort to decipher the meaning, or meanings of various encrypted symbols on display.

The elaborate medallion characteristics to rugs from the Persian town of Tafresh seemingly reflects the Zoroastrian symbol of the Sun.

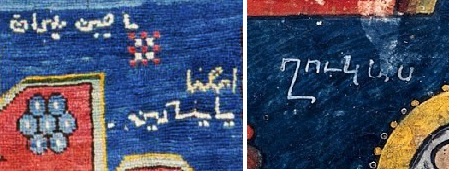

While the tribal mystical allusions are subtle, the Islamic concepts are more direct and obvious, the Armenian rug designs seem rooted in religious experience of a different kind. The nature of the relationship between the sacred and the profane here is more complex.

Upon a close comparative study of some of the most typical works from this part of the Caucasus, it may appear that apart from the most obvious imagery – crosses and less frequent churches – the religious character of the Armenian rugs are the colour scheme and the frequent inclusions of the text, Armenian or Arabic. This would suggest that the roots and the inspiration for the Armenian weavers are ancient religious manuscripts.

“ Old Armenian manuscripts show the same light and dark blue contrasts that are found in [Armenian rugs]. “

(-) Raoul Tschebull Kazak The New York Rug Society, New York 1971 p. 24

Interestingly, both Armenian and Arabic inscriptions (and dates) appear in Armenian carpets .

The study of antique rugs and their mythologies, relationship with past and present religions have become complicated and confusing with the influx of purely decorative elements in carpet design. Here the aesthetics override traditions; sacred symbols of one ethnic groups may be blended with motifs borrowed from another.

Perhaps for this reason, most rug collectors react with irate displeasure when in the face of contemporary commercial designs incorporating ‘sacrilegious’ compositions often inclusive of contrasting significance and origin.

A.G.

(1) The beauty of this rug rests in its symbolic ambiguity. The image of the mosque strikingly resembles a Christian church while the other symbolic elements can be easily interpreted as a goblet and a host. The image is further blurred by the application of a very meticulous (dazzling) weaving technique. Who was the weaver? What did she want to say?

Bacali is situated near Konya and Konya, was known in classical antiquity and during the medieval period as Ἰκόνιον (Ikónion) in Greek (with regular Medieval Greek apheresis Kónio(n)) and as Iconium in Latin. (Wikipedia)

[…] ‘… art transcends religions; there are rugs where Islamic symbols appear next to Christian cros… […]