Dickran Kouymjian

(Haig Berberian Professor of Armenian Studies, Emeritus, California State University, Fresno & Paris)

The history of Armenian carpet weaving is still a fragmented discourse known mostly within Armenian circles. Many of its basic facts are or have been challenged, or simply rejected, by determined nationalistic policies of neighboring political authorities, foremost among them the Republic of Azerbaijan and more subtly, but for a longer time, Turkey: for instance my copy of the English version of Şerare Yetkin‘s useful two volume Early Caucasian Carpets in Turkey of 1978 with its censored map blacking out the word “Armenia“.15

Such distortion or denial of artistic achievement has been aided and abetted by sycophantic scholars of the past century who succumbed to the idea that whatever was produced historically in the boundaries of a modern nation-state or, in an earlier time, an empire, must be subsumed under the name of the dominant political constituency of the country. Thus Turkish art includes everything produced within the modern borders of Turkey (though at times it is even extended to lands formerly under the control of the Ottoman Empire), even though most of the art and archi- tecture was created before the Turks arrived in the Near East and Asia Minor from distant Central Asia. Such a phenomenon is common to many nation-states. The United States has practiced the same policy: all art produced on the land is American, though with recent subtle appellations to account for understandable indignation: Native American art, African American art, and for an earlier period pre-Columbian American art.

Rugs are designated in similar ways. From the viewpoint of late medieval and renaissance Europe, they were “Oriental,“ coming from the East in the sense of Near or Middle East. There was further differentiation – Persian, Turkish, Caucasian, Anatolian, Saracen, etc. Finally, there was naming after specific localities and times closely tied to dynastic sponsoring: Isfahan, Cairo, Tabriz, Bukhara, Karabagh, Konya, Bursa, etc. But finer subdivisions became necessary, thus the proliferation of village designations, a continuous source of confusion for numerous reasons, but also designations by design or motif: animal carpets, dragon carpets, garden carpets, eagle carpets, prayer rugs, etc. These appellations challenge the notion of regional designation, at least partially.

The arts in general were classified very early, and rugs and carpets fall under the general rubric of textiles. Each medium has its own peculiarities and modes of organization.

Architecture is perhaps the most stable in terms of geographic location of production: we know with total precision where a church was erected and usually the authority responsible for it. Portable objects–painting, manuscripts, ceramics, metalwork, and of course textiles, including carpets, present the obvious problems of place, date, and attribution.

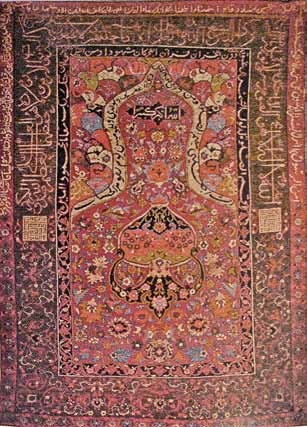

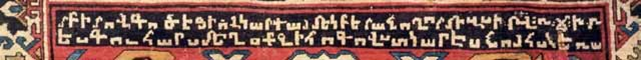

Inscriptions are of great help in determining provenance for such mobile objects, but artists did not always leave their mark. Early medieval European art was often intentionally anonymous. Rugs and carpets were very rarely inscribed, thus there is the thorny and constant problem of date and provenance. There is a fairly large group of later Islamic rugs, mostly in the Top Kapi Palace collection, with important religious inscriptions, (fig. 1)

Figure 1: Inscribed Islamic rug early 19th Century

but these are probably early nineteenth century rugs, suggested by some to have been manufactured in Hereke in an archaizing style 16; there are also many Persian rugs with inscriptions. Perhaps the largest body of carpets with inscriptions is Armenian. 17

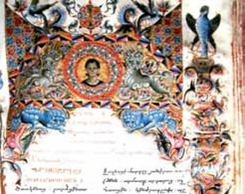

This is not an accidental phenomenon. Armenians were great practitioners of the art of the colophon – a memorial or simply an inscription of creation – used consistently in the production of Armenian manuscripts from the earliest surviving codices to the end of manuscript copying 18; no other book tradition – Byzantine, Latin, Syriac, Copt, Georgian, Hebrew, Arabic, Persian, Turkish, Ethiopian, even Slavonic – used the colophon as consistently as the Armenian.

In this exercise, usually associated with the copying of a text, the primary colophon was always that of the scribe or author, and almost always mentions the place and date of production, the name of the scribe and patron, with secondary colophons by the artist and sometimes the binder and later owners.

Thus, there should be no surprise that hundreds, probably thousands, of surviving rugs have Armenian inscriptions even though weaving an inscription is infinitely more difficult than writing one in ink on parchment or paper or carving on wood or engraving on metal. Even embroidering an inscription or stamping one on a large altar curtain is much easier than producing one on a carpet. 19

Nevertheless, the notion advanced by specialists such as Arthur Upham Pope 20 and Kurt Erdmann, later perpetuated by scholars such as Richard Ettinghausen, that such inscribed rugs were woven not by Armenians, but only commissioned by them of Turkish or other Muslim craftsmen who simply tried to copy the sketches presented to them. 21

Such pronouncements were advanced either out of a prejudice for the Islamic in all things from the Orient, or worse, out of ignorance. But this selective blindness toward Christian art, especially Armenian art, also resulted in the same aberrant schol- arship toward earlier ceramics in the Ottoman Empire, the early sixteenth century blue and white ware from Kütahya inscribed in Armenian was rejected as the work of Armenian craftsmen even though inscriptions pointed out clearly that the pots were made by Armenians for Armenians. 22

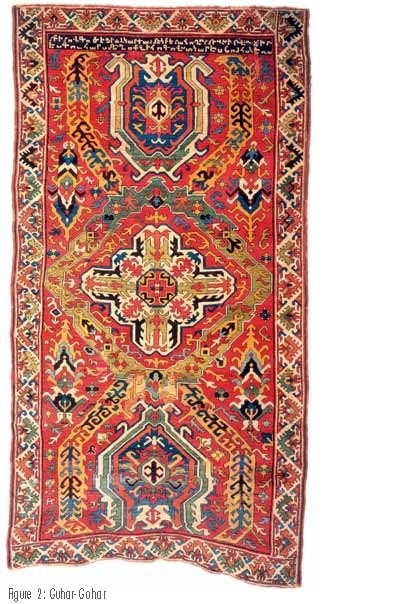

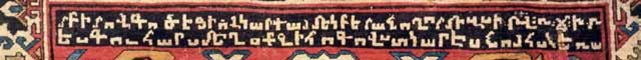

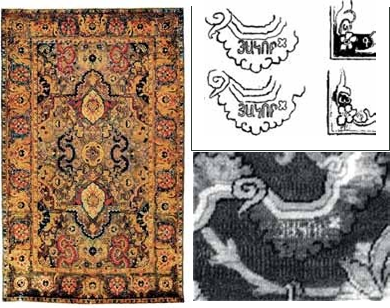

These were the same circumstances or doubts expressed toward the famous Guhar or Gohar carpet of 1699 (fig. 2), on which Gohar says in her inscription that she wove the rug: “I, Guhar/Gohar, full of sin and weak of soul, with my newly learned hands wove this rug. Whosoever reads this say a word of mercy to God for me. In the year 1148 (1699 A.D).” 23

This practice of leaving an author‘s or creator‘s inscription (hishatakaran) was practiced aggressively in the same seventeenth century in New Julfa-Isfahan where binders of manuscripts and books stamped on the outside leather covers inscriptions in erkat‘agir providing all circumstances on their crafting, including the date. 24

Gohar inscription

This was also true of silversmiths, metalworkers, ceramists, early book printers, embroiders as well as the scribes who copied manuscripts.

Very few pre-eighteenth century carpets survive and if we go back two centuries, almost nothing remains of the Oriental rug in the pre-Safavid period.

Textually, as concerns Armenian weaving, we have abundant information on local rug manufacture mostly from Arab sources, which still need to be further researched, along with the remarks of Marco Polo and other travelers. 25

Few rugs made before 1500 physically survive. The Berlin dragon-phoenix rug (fig. 3a-b) and its companion piece the Marby carpet in Stockholm are among the exceptions, thus the inordinate attention given them.

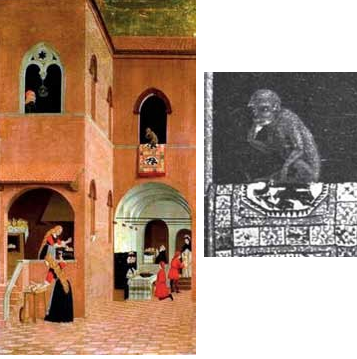

Our knowledge of carpets of the thirteenth, but especially of the fourteenth and fifteenth, centuries comes to us almost exclusively from examples found in Italian renaissance paintings. These seem to be dominated by geometric patterns, which we later identify with the so-called Caucasian carpet. Since so little has survived before the year 1500 of actual carpets our notion of what woven floor coverings looked like in western Anatolia and in eastern Asia Minor and the Caucasus is very vague. Were patterns almost exclusively geometric as seen in the renaissance paintings? The answer to such a question is almost a matter of guesswork.

Figure 3a: Phoenix and dragon carpet Anatolia 15th century Figure 3b: Marby

The Berlin carpet (fig. 3a) has no inscription and no ostensible religious symbol. The valiant attempt of Lemyel Amirian to find Armenian letters among the „hooks“ in the carpet is controversial. 26

The dating of the carpet was hypothesized by a terminus ad quem of several rugs in Italian paintings of the mid-fifteenth century (fig. 4), which seem to use the same dragon, perhaps dragon-phoenix, motif, within an octagonal frame, such as a painting by Bartolomeo degli Erri of Modena of about 1460.27

I have not studied all the earlier literature, including the work of Kurt Erdmann and others or even all of Pope‘s ideas, but I believe the hypothetical reasoning went something like this.

Since the Italian paintings of around 1450 show similar patterns we must look for a likely producer of such rugs in the Caucasus or nearby areas.

The Karakoyunlu or Black Sheep Turkmen dynasty was one possible choice because it was considered a successor to the Jalayirids, themselves successors to the Ilkhanid or Mongol rulers of Persian, who had their capital at Tabriz and an important residence in Sultaniya.

However, little Karakoyunlu art has survived. Consequently, there are problems with such an attribution and dating, though if we are to accept the carbon-14 analysis apparently made of both rugs, a fifteenth century dating is possible. 28

We are confronted, however, with numerous problems, which are far from resolved. The motif of the phoenix and the dragon has not been contextualized. There are currently two contexts:

1) that the dragon-phoenix pair is Chinese but adopted by the Yuan Mongol imperial dynasty of China after the conquest in 1279 and accession to the throne of Qubilai Khan (1279-1294), grandson of Genghis Khan, and

2) the Karakoyunlu Turkmen dynasty was the supposed indirect inheritor of the artistic motifs of the Ilkhanid Dynasty of Iran founded by Qubilai‘s brother Hulagu, two centuries earlier.

The first can be and has been demonstrated as probably valid; the second has little concrete evidence to justify it. There are a number of diverse threads that need to be examined, and it is impossible to do that in the context of this conference. But let me at least enumerate them:

- The channels through which oriental carpets reached Italy and later the Low Countries: These included the Crusades, travelers and papal emissaries to the Mongol court in the thirteenth-four- teenth centuries, and merchants, many of whom were Armenians and few, if any, of Islamic faith;

- The appearance of these oriental or Caucasian carpets (associated without tangible evidence by late nineteenth and twentieth century art historians with Islam) in Italian paintings, almost all of a Christian religious in the context, and very often with the Virgin Mary, a thesis convincingly supported by statistical data by Lauren Arnold 29;

- The history of the dragon-phoenix motif in Chinese, Mongol, and Near Eastern art. In this paper I will concentrate only on the last point.

The dragon and the phoenix are mythological creatures found in Chinese art from the earliest dynasties. They were related to the sky and thus universal.

Neither was considered a menacing animal, unlike the dragon in the West, something not understood by many who have written on the dragon-phoenix carpet or other objects with this motif.

In China both these creatures were considered benevolent. In time, the dragon became the symbol of the emperor and the phoenix, the empress.

Up to the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the Chinese did not think of them in conflict. Thus, it is dangerous to insist that the animals in he Berlin carpet are battling each other, unless we move its date to the later Ming period, sixteenth or even seven- teenth century, when Ming art (fig. 5) places them together fighting over a pearl. 30

This leaves too many centuries between the renaissance paintings and the later Ming to imagine the continuity of such a static rendering of an animal motif from a much earlier period.

Furthermore, except for a single bronze only recently published, 31 there are no examples of the two animals together on the same object in Chinese, Mongol, or Islamic art until after the fall of the Yuan Dynasty, that is after the fourteenth century, but more probably later in both China and Islamic lands of the Near East.

The introduction of Chinese dragons and phoenixes in the Near East first occurs through a series of large luster tiles (fig. 6) used in the private and ceremonial chambers of the summer palace of the Ilkhanids at Takht-i Suleyman southeast of Tabriz and west of Sultaniya. 32

The tiles are undated and without inscriptions, but on the same walls there are other smaller and differently shaped tiles, probably affixed at the same time, with dates of 1271 to 1275/6.

These impressive tiles were arranged in long rows alternating dragons and phoenixes. There are no known tiles of the thirteenth century that show the two celestial animals on the same ceramic.

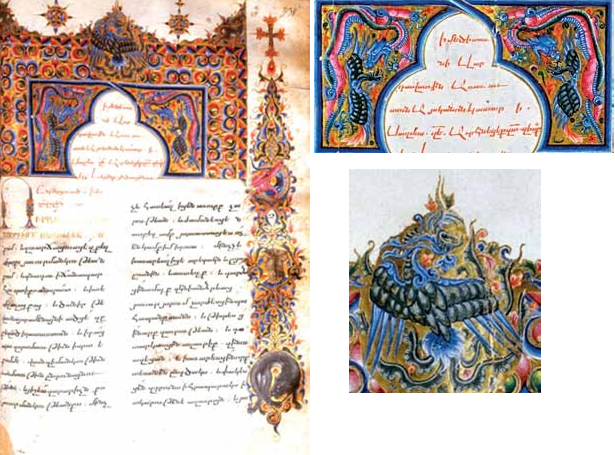

The earliest representation (figs. 7a) of the dragon and phoenix together is in a headpiece for the feast of the Transfiguration in the famous Armenian Lectionary of Het‘um II dated 1286.33

This is not an isolated rendering, in this case painted twice (fig. 7b) in the spandrels of the arch above an incipit.

On top of the headpiece there is a large heraldic phoenix (fig. 8a), which dominates the scene; it is nearly identical to the rebirth of a phoenix (fig. 8b) from a Jin Dynasty (1115-1234) silk brocade with gold thread.34

In the same Lectionary, there is another headpiece for the reading of the Annunciation with a picture of Christ Emmanuel, (fig. 9) guarded on both sides by Chinese lions and surrounded by Chinese lotus flowers and the Buddhist wheel of the law. 35

This accumulation of Chinese motifs was not just casually added to the luxuriously illuminated royal Lectionary along with other artistic elements from the Byzantine and European traditions.

These Far Eastern motifs are carefully integrated into a statement of sovereignty (figs. 8b, 9).

The crown prince Het‘um was honoring his father and mother, King Levon, symbolized by the youthful Christ guarded by the protective lions of Buddha, while the heraldic phoenix of the other headpiece represents Queen Keran, the great patron of the arts.

The dragon and phoenix together represent the king and queen of the realm ruling over an Armenia at peace as depicted in portrait miniatures of Gospels of 1262 and 1272 (figs. 10a-b). 36

Furthermore, these animals and their symbolic interpretation were clearly and perfectly understood among the artists of the court confirmed by such details as the number of claws of the dragons.

In China the imperial dragon was always represented with five claws, other members of the royal family were allowed dragons of four claws, while noble vassals were permitted the use of three claws; the Lectionary dragons have four.

Thus, (fig. 11) in a Gospel executed in 1289 for Bishop John, brother of King Het‘um I and the uncle of King Levon and Het‘um II, who has a silk lining on his liturgical robe with a Chinese dragon on it with just three claws. 37

How did the Armenian royal court acquire Chinese objects – silks, ceramics, perhaps even paintings — with such designs? The following, discussed in detail in an earlier study, 38 are the most likely sources:

- through the exchange of gifts between Armenian aristocracy and the Great Khan in Qaraqorum and numerous visits to the Ilkhanid court in Sultaniya and probably even Takht-i Suleyman. The most famous of these was the journey of Smbat sparapet to the capital of the Great Khan (1247- 1250), which was followed by another trip of his brother King Het‘um three years later (1253-1256).

The sources speak of the exchange of royal gifts, which I have discussed in detail in the articles already cited.2.

2. by trade on the silk route which passed through Greater Armenia and Cilicia.

Whatever the source of objects which supplied the Chinese motifs to the rulers and religious leaders of Armenia, they were carefully used and their meaning clearly understood already in the 1280s.

Islamic art began borrowing chinoiserie in the 1290s, but very timidly with lotus flowers and Chinese cloudbands a decade or two earlier.

In the early fourteenth century these motifs appear more abundantly in such works as the Jami al-tawarikh of Rashid ad-Din and in some Shahnamehs. But finding the dragon and phoenix alone or later together is rare and late and seldom with a clear symbolic interpretation such as its use in thirteenth-century Armenia. 39

If the Berlin dragon-phoenix rug and the Marby carpet (figs. 3a-b) were royal commissions of the Türkmen Karakoyunlu or even Ottomans, as some have suggested, one would need to contextualize their use.

Furthermore, there would need to be some supporting evidence that the Karakoyunlu Jahanshah (1437-1467), the most likely ruler under which they might have been woven, encouraged such Sino-Mongol motifs in his court art.

If, however, these rugs were somehow associated, even indirectly, with Cilician art, one would expect an earlier, perhaps fourteenth century dating.

I have not had access to articles that discuss the carbon-14 dating of the Berlin carpet and have little idea of the parameters of such dating, except the usual remark that there is a 200-year tolerance. Unfortunately, we have little concrete, irrefutable evidence that Armenians wove such animal rugs, but this is equally true for Persian, Turkmen, or Ottoman weaving of the early centuries.

There are of course abundant textual references to Armenian carpet weaving in Arab, Ottoman, medieval and early modern European travel accounts.

The technical skill of Armenian rugs and their very diverse and innovative design mastery is underlined by inscribed and dated carpets from the early seventeenth century.

Such items, though dating two centuries after experts imagine the Berlin carpet was woven, offer the kind of precise data lacking in most other traditions. The few surviving carpets attributed to before 1500 are hard to date precisely; those pictured in Italian paintings of the Renaissance are assigned the date of the painting or to some indeterminate number of years before.

Neither of these resources is much help in determining who wove them and precise geographical information on where they were crafted. In this respect, solid evidence is found for instance in the inscribed Guhar carpet of 1699 or 1700 (fig. 2), universally accepted as a magnificent textile .40

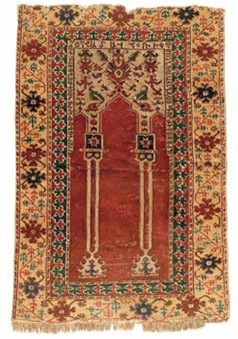

There is an earlier inscribed prayer rug formerly in a private collection in Vienna (fig. 12), current whereabouts uncertain, but published in color with a dated inscription probably of 1512. 41, and another fragment with an inscription of ca. 1600. 42

Figure 12: Riedl, probably 1512

Armenian prayer rug

One perhaps should also mention the inscribed carpet of 1592 from Julfa on the Arax, current whereabouts unknown, but copied in a new weave in Bulgaria in 1939-1940. 43

In the oral presentation I also mentioned the Yakob carpet, a large „polonaise“ type Safavid rug dated by style to 1620-1625 now in the Art Gallery of South Australia in Adelaide (figs. 13), signed in the upper right and lower left, Yakob/Hakob, in very finely woven Armenian majuscule (erkat‘agir), almost invisible to the naked eye, and in the extreme corners his initials: Y. and G. Yakob was certainly the weaver of the rug, because if he were the patron, his name would have appeared more prominently.

It is now clear to me that this is a counter-example, though still important to demonstrate Armenian involvement in rug design, weaving, and marketing.

The rug in Australia, originally part of the Bowman collection in Paris, was not woven by a mysterious Armenian working in Isfahan-New Julfa in the time of Shah Abbas, but rather Hagop Kapoudjian, established in Paris and considered by many as one of the last masters of the Kum Kapi rug making school of Constantinople.

I had written about him some years ago 44 but failed to make the associa- tion with the „Hagop“ signature of this rug in a paper given in Zamość, Poland in 2010 on inscribed Armenian objects. 45

Rather it was Berdj Achdjian of the Achdjian Gallery in Paris who recently informed me that his father Albert, who established the Oriental rug shop on rue Miromesnil, had always considered Kapoudjian as his master when they worked together in 1929-1930. 46

Conclusion

The attribution of non-inscribed and undated artifacts is done through stylistic analysis and comparisons with other objects. Historical context and the previous use of motifs are also credible markers for establishing provenance. No rug weaving tradition other than the Armenian can bring along with its claim of proprietorship:

1) a long and well-documented history of weaving practice; 2) the very precocious (really unique) earliest instance of the joining together of these Chinese animals on a single object; and 3) a de- monstrable understanding of what the dragon and phoenix represented to the Chinese and Mongols.

As a closing observation, in the late 1970s, when I first reported on the dragon-phoenix motif in the 1286 Lectionary, suggesting that the animals were in conflict, as is the case in the later Ming period, my colleagues of Chinese art reprimanded me because they said that was not the case. After I corrected my remarks years later, I was told that there was no precedent in medieval Chinese art of the animals together, so I claimed, without opposition on their part, that Armenian artists were the first to bring them together. It was only a few years ago that professor Lukas Nickel wrote from London that he found a Chinese report on a number of recently excavated tombs in one of which was a bronze mirror (fig. 14) with the dragon and phoenix together that could be dated to 1093.47 Consequently, at least one example of such a dragon-phoenix combination is known dating nearly two centuries before the Armenian specimens and four before the Ming. Prof. Nickel cautioned, however, that this was in the Liao Dynasty and the Liao were not Chinese; thus, Central Asia might be the place where the animals were joined on an ordinary, rather than an imperial, object.48 This raises the question that if the mirror iconography was unknown in China or not popularly used, therefore inaccessible to Armenians, (fig. 6) is it not then possible that in 1286 Armenian artists or their royal patrons who had seen the separate but juxtaposed dragon and phoenix tiles at Takht-i Sulayman during a formal visit had independently brought together (fig. 15) the celestial symbols in the headpiece as they did later in the Berlin carpet in precisely the same position?

- Şerare Yetkin, Early Caucasian Carpets in Turkey, 2 vols., London: Oguz Press, 1978, map on pp. viiiSee the long discussion in The Topkapı Saray Museum, Carpets, translated, expanded and edited by J. M. Rogers from the original Turkish by Hülye Tezcan, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1987, pp. 17, 26-30.

- Lucy Der Manuelian and Murray Eiland, Weavers Merchants and Kings: The Inscribed Rugs of Armenia, Forth Worth, TX, 1984; Dickran Kouymjian, „ Les tapis à inscriptions arméniennes,“ in H. Kévorkian et B. Achdjian, Tapis et textiles arméniens,

Marseilles, 1991, pp. 247-253, available on web: http://armenianstudies.csufresno.edu/faculty/kouymjian/articles/index.htm;

Murray L. Eiland, Jr., editor, Passages. Celebrating Rites of Passage in Inscribed Armenian Rugs, San Francisco: Armenian Rugs Society, 2002.

- Much has been written on the subject, but a clear explanation is found in the introduction to Avedis K. Sanjian, Colophons of

Armenian Manuscripts, 1301-1480. A Source for Middle Eastern History, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1969, pp. 1-41.

- Though inscriptions on carpets like that in Fig. 1, a late Hereke type, seem perfectly rendered.

- Arthur Upham Pope, “ The Myth of the Armenian Dragon Carpets,” Jahrbuch des asiastischen Kunst, II,1925, pp. 147-158. The

article was challenged by Armenag Sakisian „Corrections to ‚Myth of Armenian Dragon Carpets,‘“ Syria 9/3 (1928), p. 230, and in the same issue Sakisian published, „Les tapis à dragons et leur origine arménienne,“ pp. 238-256, to which Pope in turn

responded: „Les tapis à dragons. Réponse de M. U. Pope à l‘étude de M. Sakisian,“ Syria 10/2 (1929), pp. 181-182. See also,

Harutiun Kurdian, ‘Corrections to Arthur Upham Pope’s “ The Myth of the Armenian Dragon Carpets”’, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1, 1940, 65-67.

- I remember a personal conversation with Prof. Ettinghausen in his office at the Metropolitan Museum in New York in the mid-1960s where he made this precise pronouncement with conviction. In most domains of Islamic art he was excellent in his pronouncements. A decade after I published an important essay he sent me in honor of his close friend George Miles,

Richard Ettinghausen, „Arabic Epigraphy: Communication or Symbolic Affirmation,“ in Dickran Kouymjian, editor, Near Eastern Numismatics, Iconograpy, Epigraphy and History: Studies in Honor of George C. Miles, Beirut: American University of Beirut, 1974, pp. 297-317. His position on Oriental, especially Armenian, rugs followed closely that of Arthur Pope‘s, not surprising

since Ettinghausen came to the United States in 1934 for a position in the Institute of Persian Art and Archaeology that Pope had established in New York, for which see Robert Hildenbrand, „Richard Ettinghausen and the Iconography of Islamic Art,“ in Stephen Vernoit, ed., Discovering Islamic Art: Scholars, Collectors and Collections 1850-1950, London: I.B. Tauris, 2000, pp.

171-181; cf. Yuka Kadoi, „Arthur Upham Pope and his ‚research methods in Muhammadan art‘: Persian Carpets,“ Journal of Art Historiography, no. 6 (June 2012), pp. 1-12.

- The pioneering work was done by John Carswell, with Charles Dowsett for the Armenian texts, Kütahya Tiles and Pottery from the Armenian Cathedral of St. James, Jerusalem, 2 vols.,Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972, repr. Antelias, 2005; for a reexamina

tion of the evidence, Dickran Kouymjian, „Le role des potiers arméniens de Kütahya dans l‘histoire de la céramique ottomane,“ Des serviteurs fidèles. Les enfants de l‘Arménie au service de l‘État turc, Maxime Yevadian, ed., Lyon: Sources d‘Arménie, 2010, esp. pp. 69-71, available on web, see note 3 above.

- Dickran Kouymjian, „Le tapis « Gouhar » [« Gohar »] ,“ Arménie : la magie de l’écrit, La Vieille Charité, Marseille, catalogue,

- http://www.flickr.com/photos/26911776@ N06/sets/72157605221104561/, especially interesting are her statistics of the

context in which the rugs from the Near East are painted, and Dr. Arnold‘s excellent blog, which contextualizes these rugs within a Christian setting.

- By way of example, the motif is very clear on a yellow lacquer dish the motif in the National Palace Museum in Taiwan from the

Chia-ching reign, 1522-1566, of the Ming Dynasty.

- It was found in a tomb burial of 1093 in Xuanhua, Hebei, Excavation Report of the Liao Dynasty Frescoed Tombs at Xuanhua:

Report of the Archaeological Excavation from 1974-1993, Beijing: Cultural Relics Publishing House, 2001, vol. 1, p. 49. Details can be found in Dickran Kouymjian, “Chinese Motifs in Thirteenth-Century Armenian Art: The Mongol Connection,” Beyond the Legacy of Genghis Khan, Linda Komaroff, ed. (Leiden: Brill, 2006), pp. 322-324, available on web, see note 3 above; for

illustrations, idem, “ The Intrusion of East Asian Imagery in Thirteenth Century Armenia: Political and Cultural Exchange along the Silk Road,” The Journey of Maps and Images on the Silk Road, Philippe Forêt and Andreas Kaplony, eds., Leiden: E. J. Brill, 2008, p. 127, fig. 6. 7b, available on web, see note 3 above; idem, “Chinese Dragons and Phoenixes among the Armenians,” in Civilizational Contribution of Armenia in the History of the Silk Road, Erevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences, 2012, published 2013, p. 252, fig. 6, available on web, see note 3 above.

- The closest in feeling are on the large luster titles, both dragons and phoenixes, but never together on the same tile, and for

the phoenix the eight-pointed star tiles in lajvardina; Linda Komaroff and Stefano Carboni, The Legacy of Genghis Khan, Courtly Art and Culture in Western Asia, 1256-1353, New York: Metrolopitan Museum and Yale University, New Haven, 2003, no. 99,

fig. 97 dragon from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, no. 100, fig. 100, phoenix from the Victoria and Albert Museum. During the exhibition „The Legacy of Genghis Khan“ (2003) at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Linda Komaroff and her staff set up

an entire wall of these tiles or their reproductions mixing dragon and phoenix tiles somewhat like the reconstruction, cf. for the se same or similar phoenix and dragon tiles from Takht-i Sulayman, Dickran Kouymjian, “Chinese Influences on Armenian Minia ture Painting in the Mongol Period,” Armenian Studies/Études arméniennes: In Memoriam Haïg Berbérian, Dickran Kouymjian, ed., Lisbon: Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, 1986, figs. 10 –14, available on web, see note 3 above.

- Erevan, M979, Lectionary of Prince, later King, Het‘um II of 1286, fol. 334. The manuscript has accumulated a large number of studies in recent years, with all of the hundreds of miniatures and marginal decorations illustrated in Irina Drampian,

Lectionary of King Het‘um II, text in Armenian Russian, English, Erevan: Nairi, 2004. For a detailed description and discussion of the dragon-phoenix headpiece, see Dickran Kouymjian, „Chinese Influences,“ pp. 426-431, figs. 3a-3d; idem, „Chinese

Dragons and Phoenixes among the Armenians,“ pp. 232-234, figs. 2-4.

- Cleveland Museum of Art, John L. Severance Fund (1994.292), James C. Y. Watts and Anne E. Wardell, When Silk Was Gold, Central Asian and Chinese Textiles, New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1997, no. 31, pp. 118-119 illus.

- Erevan, M979, Lectionary of Prince, later King, Het‘um II of 1286, fol. 293, lection for 7 April, the Annunciation to the Virgin;

Kouymjian, „Chinese Influences,“ 421– 425, figs. 2a–2e; idem, „Chinese Motifs,“ pp. 314-317, ps. 24-25, figs. 58, 61-63; idem,

„Chinese Dragons and Phoenixes,“ pp. 231-234.

- Jerusalem, J2660, Gospel, 1262, f.228, T‘oros Roslin: Prince Levon & Keran; J2563. Gospel, 1272, f.380 : King Levon & Queen Keran with children, the future Het‘um II next to his father, under a Deisis with the Virgin and John the Baptist flanking Christ, see Kouymjian, „Chinese Motifs,“ pp. 319-321; idem, “ The Intrusion of East Asian Imagery,“ pp. 127-128.37.

- Discussion of this question in Kouymjian, „Chinese Influence,“ p. 431; idem, „Chinese Motifs,“ 308-309, 314, 320 ; idem, Dragons and Phoenixes, p. 234, note 21. On the question of such attributes, see Tomoko Masuya, „Ilkhanid Courtly Life,“ The Legacy of Genghis Khan, pp. 96-97, cf. Kouymjian, „Chinese Motifs,“ pp. 319-320, notes 74-75.

- Full details can be found in Kouymjian, „Chinese Influence,“ pp. 415-417, 429-435, 449-456.

- Formerly in Vienna, published by Alois Riegl, Ein orientalischer Teppich vom Jahre 1202 n. Chr. und die ältesten orientalischen Teppiche, Berlin: 1895, frontispiece in color and pp. 7-9; cf. later by Babken A ak‘elyan, K‘alak‘nere ev arhestnere Hayastanum IX-XIII darerum (The Cities and Crafts in Armenia in the Ninth to Thirteenth Centuries), vol. I, Erevan: Academy of Sciences, 1958, pp. 292-293 with colored plate tipped in between them; prayer rug with a long Armenian inscription and the date

961/1512, read incorrectly as 651/1202 by Riegl and by A ak‘elyan following V. T‘emur yan. The letters might be read as

(961 = 1512), but most probably not (651 = 1202); the rug‘s design, decoration, and organization make such an early date almost impossible. See also the discussion on the type in Volkmar Gantzhorn, The Christian Oriental Carpet, Cologne, 1991, German, French, and English editions, pp. 481-484, the author sees the date as 1602 or (1) 651. Earlier the dating was also questioned,

since the rugs pattern is much later, Murray L. Eiland, „Handwoven Rugs of the Armenians,“ in Lucy Der Manuelian and Murray L. Eiland, Weavers, Merchants and Kings: The Inscribed Rugs of Armenia, Fort Worth, TX: Kimbell Art Museum, 1984, p. 56, fig. 24.

- Former Paris, Baranovicz Collection, Gantzhorn, The Christian Oriental Carpet, p. 394, fig. III. 530, believes the fragment with a difficult Armenian inscription for Julfa on the Arax rather than New Julfa-Ispahan.

- London, the Avakian family, Manya Ghazarian, Armenian Carpet, English and Armenian, Erevan: Erebouni, 1988, pp. 6-7.

- Dickran Kouymjian, “ Textiles arméniens: une riche palette,” Trames d’Arménie : tapis et broderies sur les chemins de l’exil

(1900-1940), Muséon Arlaten, 16 June 2007– 6 January 2008, catalogue Dominique Serena, ed., Arles, 2007, p. 32 on Kapoud jian, citing the volume by George F. Farrow and Leonard Harrow, Hagop Kapoudjian: The First and Greatest Master of the Kum Kapi School, London: Scorpion Publications, 1993.

- Dickran Kouymjian, “Reflections on Objects with Armenian Inscriptions from the Pre-Twentieth Century Diaspora,” Series

Byzantina, IX (2011), pp. 107-108, figs. 9a-d, available on web, see note 3 above. A discussion of the carpet with reference to earlier literature can be found in M. Wenzel, „Carpet and Wall-Painting Design in Persia. An Armenian-inscribed ‚Polonaise‘

Carpet,“ Apollo (1988 July), pp. 4-11, though the author was unaware of its being woven nearly three centuries after Shah Abbas

in the Safavid style, but in Constantinople, or perhaps even in Paris.

- Personal discussions and email exchanges, 15-17 April 2014, during which he drew my attention to the book about Kapoudjian, which I had totally forgotten about.

- Excavation Report of the Liao Dynasty Frescoed Tombs at Xuanhua – Report of Archaeological Excavation from 1974-1993, Beijing: Cultural Relics Publishing House, 2001, vol. 1, p.

- Details in Kouymjian, „Chinese Motifs,“ Addendum on the Dragon-Phoenix Motif, pp. 322-324.