The main aim of this blog is to share the passion for carpet weaving arts around the world. The articles published in this blog have a very generic character with no claims to academic authority.

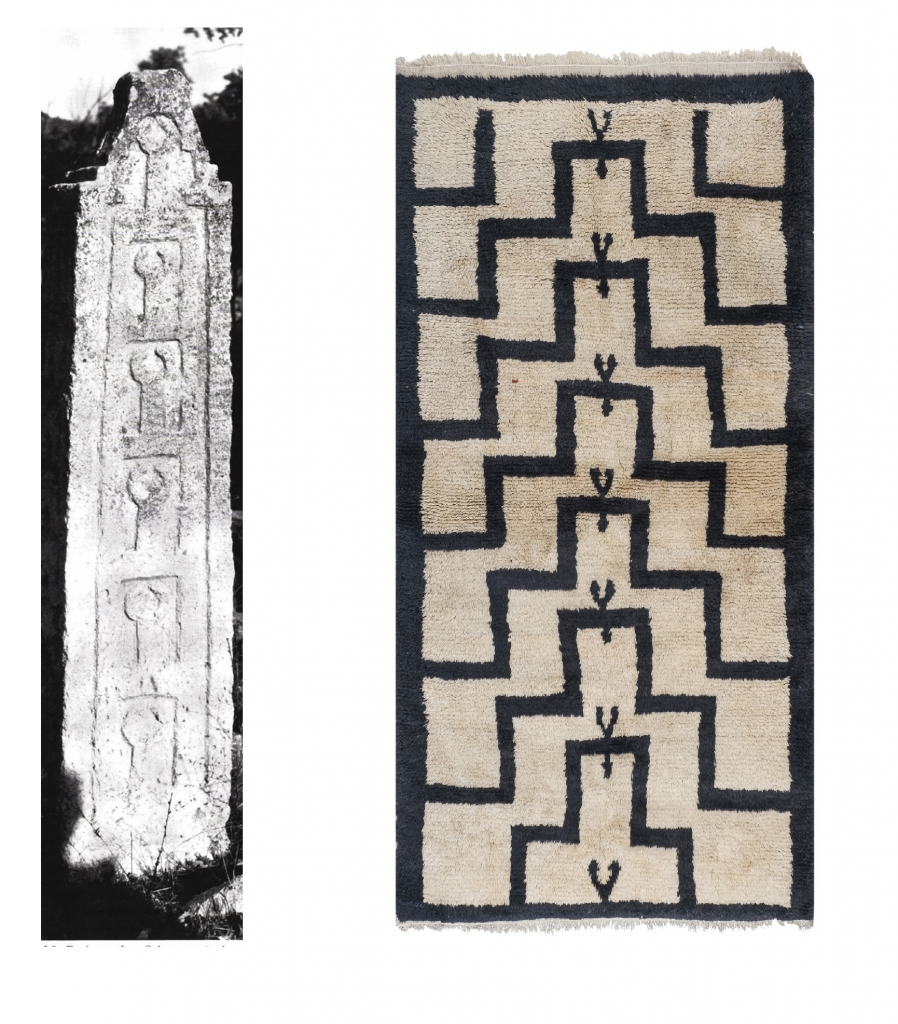

The origins of the ascending arches design in Anatolian rugs, known commonly as ‘bacali’ from chimneystack in Turkish, may go as far back as mankind’s Neolithic period.

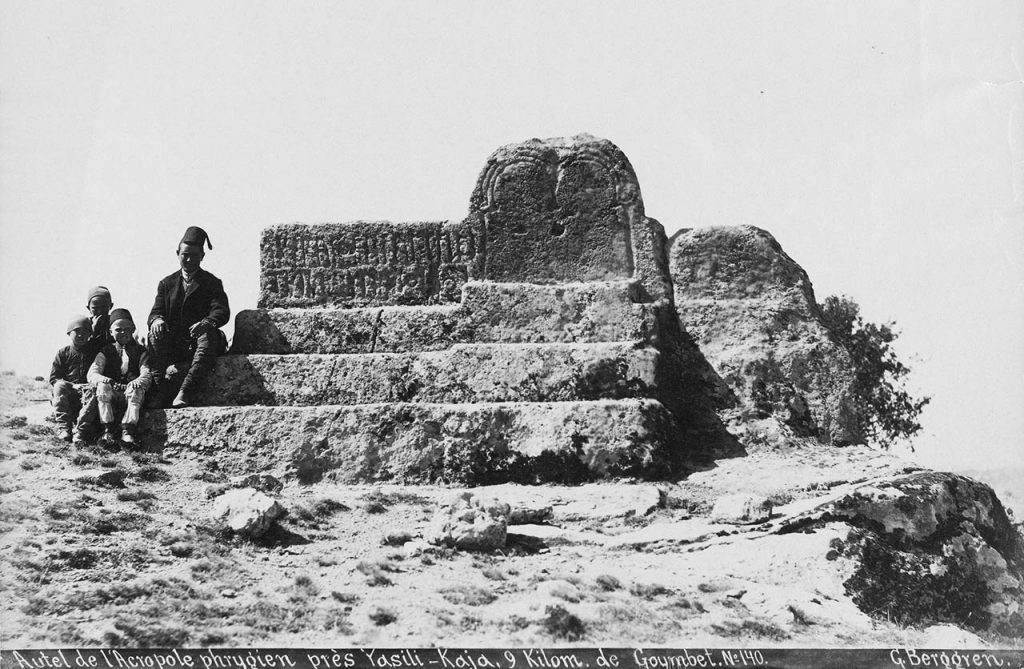

There is a clear resemblance between the design and the many step-monuments, altars related to the ancient cult of Cybele, the goddess of gods.

Arguably, the motif of the step-monuments appearing in numerous village rugs (tulu) was adopted and integrated into the Islamic faith in the course of more recent history.

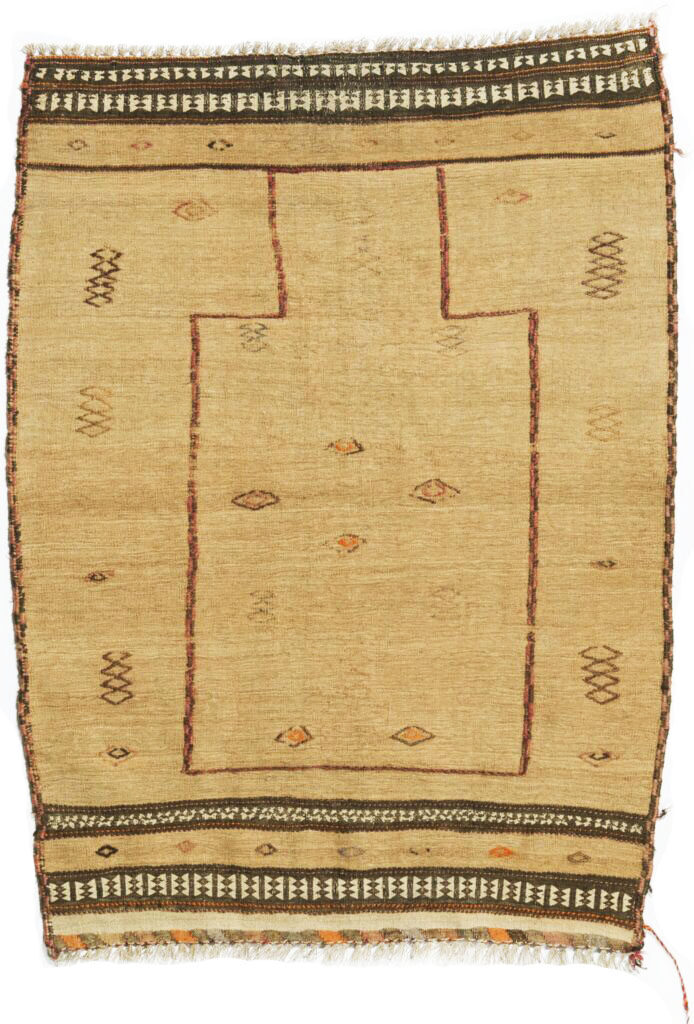

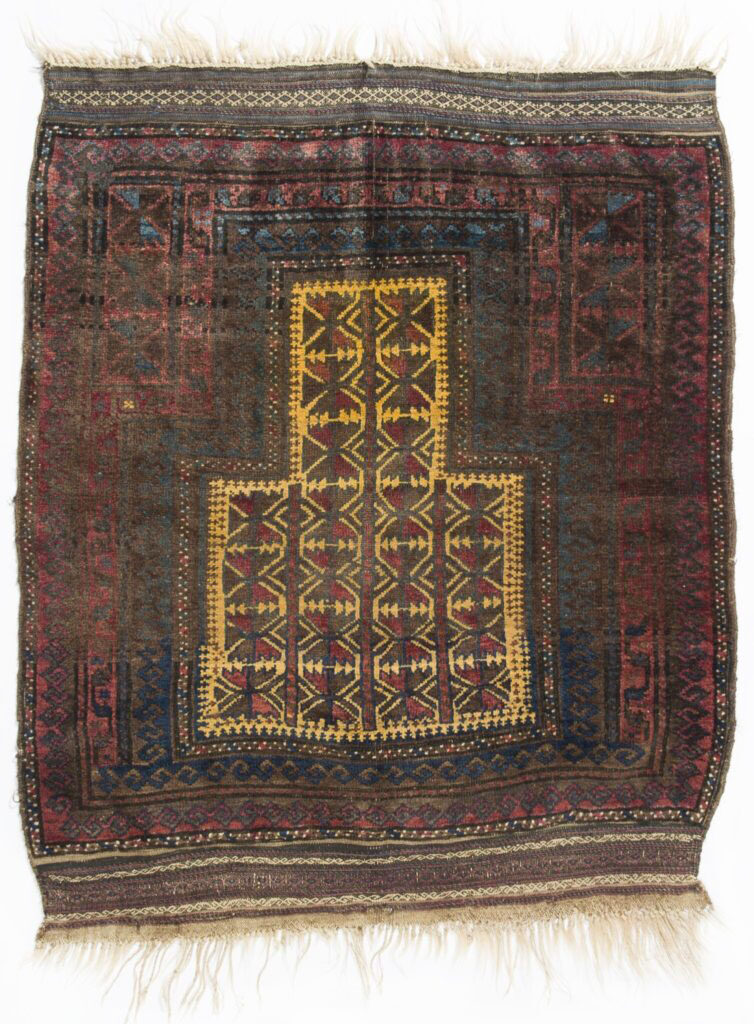

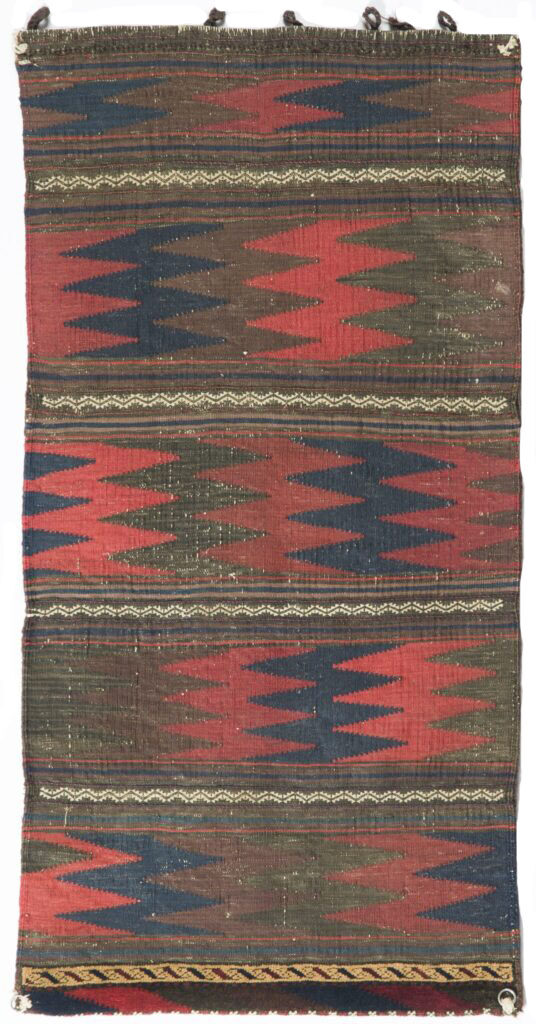

The antique kilim from the collection of Sonny Berntsson (below) discussed earlier, best illustrated my thesis.

The same motif appears also in the contemporary Central Anatolian kilim formerly in the author’s collection

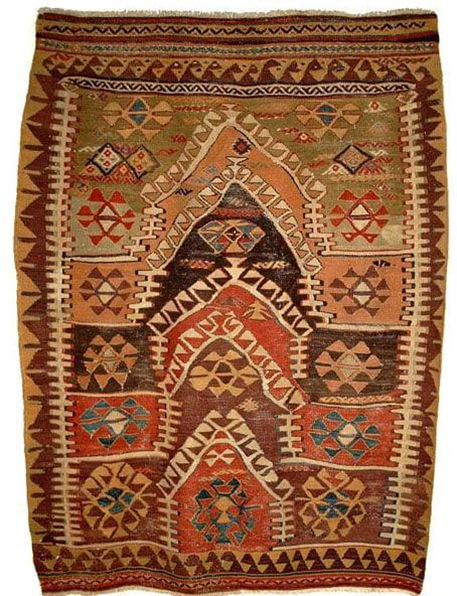

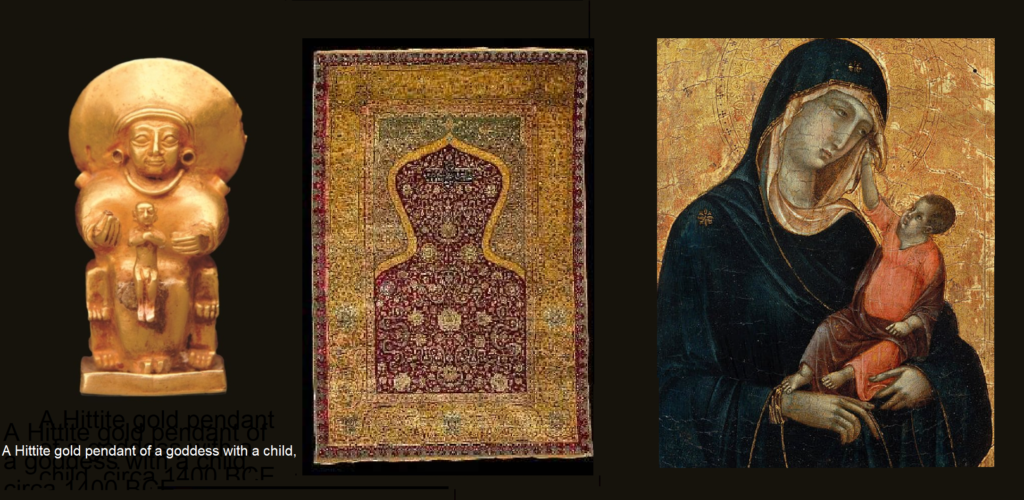

However, there seems to be more; if viewed from the side (profile) these monuments may be reflected in the motif of stepped mihrab which is very common in many Islamic prayer rugs, but most frequently in those from the areas of Anatolia where such step-monuments are a common sight.

The geometry of Cybele’s altars proved relatively easy to execute in coarse wool works by nomads and villagers, however, sections of these altars may have given rise to more than one form of the Islamic niche.

The top part of the altar, perhaps a throne, appears to be replicated in numerous prayer rugs across Islamdom and beyond.

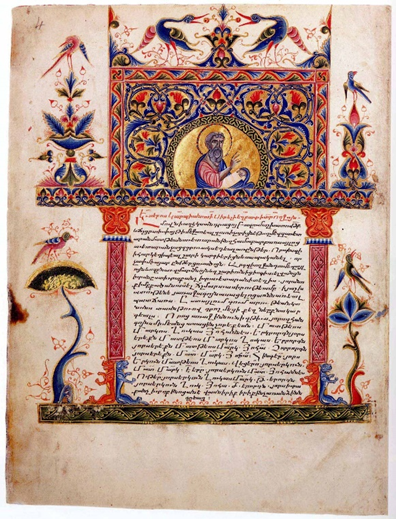

Early Armenian Christian manuscripts feature similar forms which perhaps also are reflected in the image of the aureole.

This may suggest that the ancient monuments left scattered across Anatolia following the fall of the Hittite empire may have provided the basis for the visual continuation of the objects of worship by various ethnic and religious groups inhabiting the area.

The small gold pendant of a goddess with a child, circa 1400 BCE from Central Anatolia. (MMA 1989.281.12) may have been an archetapal model,

a proto-madonna figure which later gave rise to the cult of mother and child.

Only through the study of art, in the earliest forms, may we unearth the foundations of religion.

Piotr Wesolowski

Berber Symbols and their Meaning

Long overlooked, perhaps even neglected, Berber rugs have of late become a subject of intense scholarship.

A name that stands out in the context of these studies is that of the Swiss scholar, Bruno Barbatti.

His seminal work Berber Carpets of Morocco: The Symbols: Origin and Meaning is a result of years of his fieldwork in the Atlas Mountains and the Saharan side of the Atlas Chain in Morocco.

Barbatti’s scholarly focus was the language of symbols, the enigmatic signs that appear in Berber textiles.

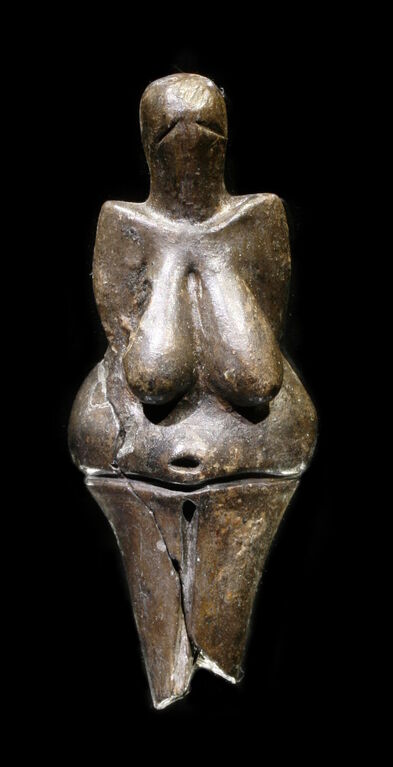

The repeated motifs, believed to date to Neolithic or perhaps even Paleolithic era of human development, suggest clearly the presence of an ancient, complex system of meaningful symbols.

Barbatti’s scrupulous semiotic approach opened a gate to a world of magic, and suddenly, the decorative function of primitive floor coverings acquired another dimension.

The Berber rug is a protector, a vessel of hope, a conveyor of wishful thinking, and a repository of pain and fear.

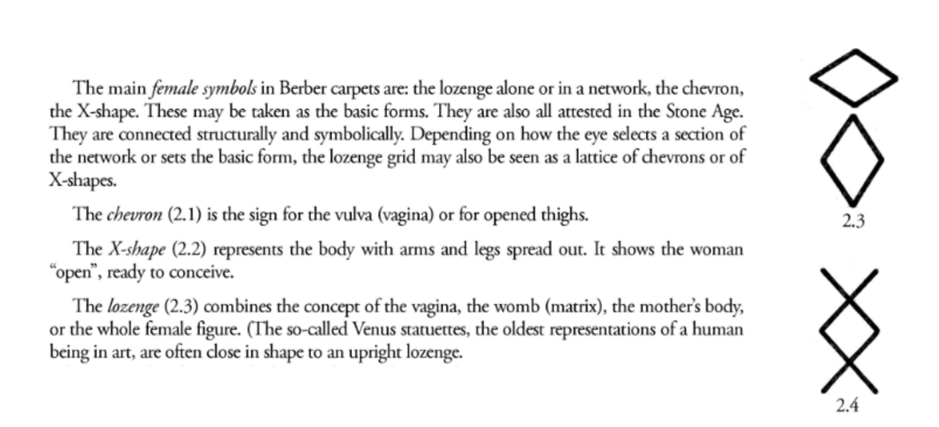

The symbols observed and analysed by Barbatti are rooted in the ancient cult of fertility; they represent, for the most sexual organs, and if presented out of their anthropological context, they may prove obscene.

Relatively explicit, if paid close attention to, vulva and phallus images may not necessarily appeal to Western consumers, least of all to those in search of but attractive home décor utilitarian objects.

Scholars however view this complex system of fertility symbols as erotic mysticism which is devoid of sexual connotations.

A Berber carpet possess power; it is not just but an attractive a floor covering.

This power is endowed to it by the weaver, and the loom is the symbolic door to an outer reality.

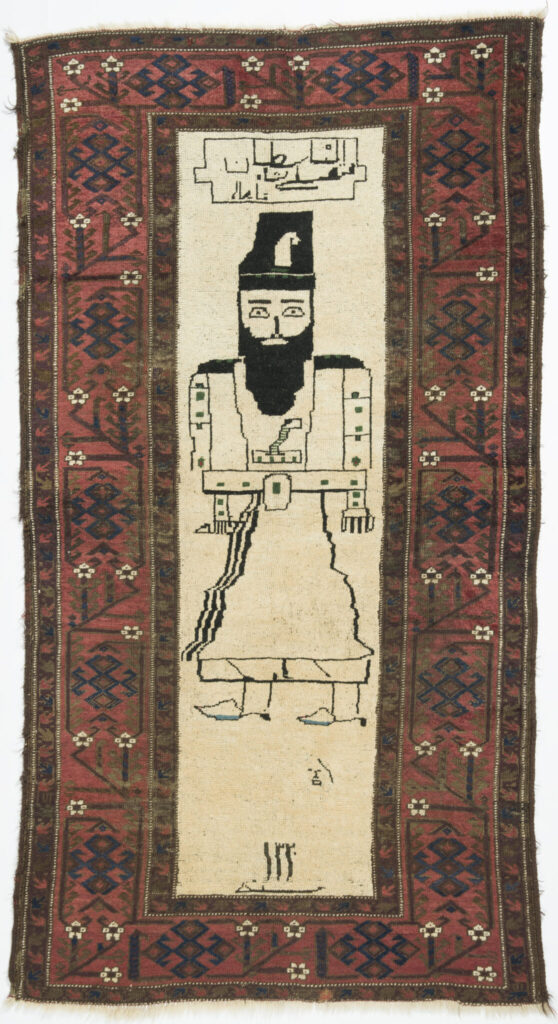

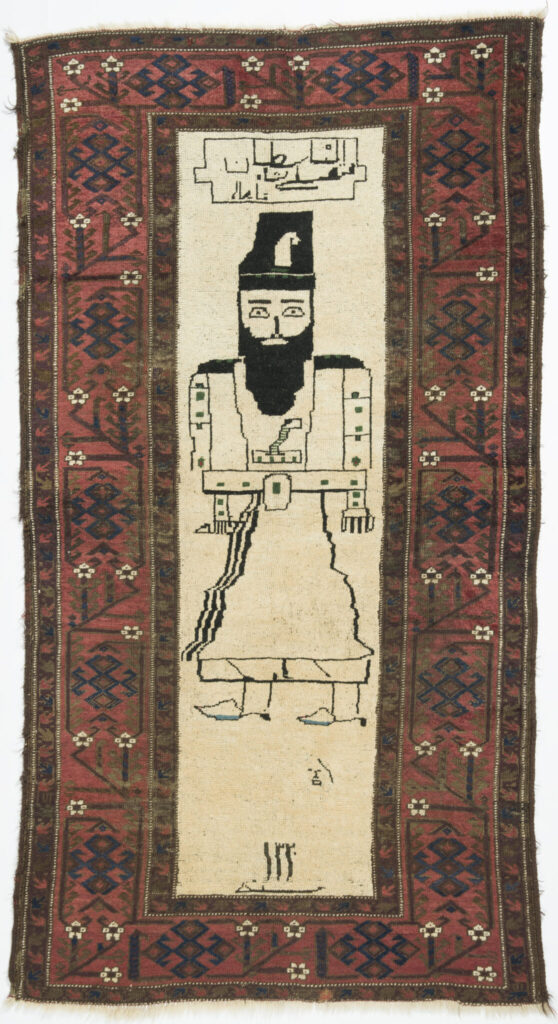

In the instance of this small Berber work by an anonymous Amazigh woman from an unidentified tribe below expresses her hope for a ‘healthy’ childbirth.

It speaks of her fear of pain and preoccupation. It is a supplication, a plea for assistance projected clearly in an unusually realistic drawing of hands, presumably those of midwives but perhaps metaphorically those of guardian spirits.

The central image in the small rug in question is the lozenge and within it, a small seemingly floral element.

The lozenge, a basic geometric form that frequently appears in Berber carpets (vertically and horizontally in kilims) represents female sexual and childbirth organs:

The motif of hands, the most realistic element in the rug, confirms explicitly what may otherwise be viewed as Barbatti’s theory, his suppositions, and not the actual language of symbols.

This small rug may in fact serve as evidence of the secret universe of the Berber women and their very intimate relationship with the loom.

Piotr Wesolowski

The motif of hands, the most realistic element in the rug, confirms explicitly what may otherwise be viewed as Barbatti’s theory, his suppositions, and not the actual language of symbols.

This small rug may in fact serve as evidence of the secret universe of the Berber women and their very intimate relationship with the loom.

Piotr Wesolowski

This is a Rugs News and Design Publication August 2023

Quotations from: Bruno Barbatti Berber Carpets of Morocco: The Symbols: Origin and Meaning

It is argued that most Caucasian rugs that appeared on the Western market at the beginning of the 20th century, were produced circa 1880.

It is however but an arbitrary date. It is not sure when exactly the regional cottage industry took root in this isolated and relatively inaccessible area, and there are very few rugs to be found predating the 1880s; yet many merchants insist that the 1880s were the apex of the industry that always existed in the Caucasus.

Possibly, , in fact, with Russia’s ambitious plansof revitalizing the newly annexed territories (1860s), the moribund industry of the Persian Kajars khanates, enjoyed its own glorious period of Renaissance.

This would in some way explain this meteoric phonemonon, the short-lived and yet so fascinating rug production of the turn-of the-20th-century Caucasus.

The origins of this phenomenion are as mysterious as its end; the dearth of early 20th century may suggest that such rugs were no longer produced.

It also argued that the decline or perhaps the end of the Caucasian phenomenon was brought about by

a) the demand for larger format rugs on the US market (Raul Tschebull)

b) the outbreak of WWI (Yuka Kadoi)

c) the Bolshevic revolution.

Some evidence however suggests that the production of good quality rugs continued in the Caucasus long after the Soviet October revolution of the 1917 while there is still not enough evidence suggesting solid weaving tradition in the popular Caucasian 19th c. rugs style predating the 1880s.

Ironically, while the ever-dexterous merchants continually unearth greater numbers of the so-called ‘earlier pieces’ that is those going back as far as the beginning or middle of the 19th century, the early 20th century Caucasian rugs whose production is well documented (read William Dunbar HALI issue 204) seem to have completely disappear.

Piotr Wesolowski

Note: 1,2,3 are Arabic numeral which we adopted to replace Roman numbers I,II, III, etc

The Arabs, on the other hand, whose trade with the Subcontinent was always of great economic importance, adopted the Indian numerals ١,٢,٣,٤,٥.١٠ which, unlike any other Arabic texts, are are read from the left to the right.

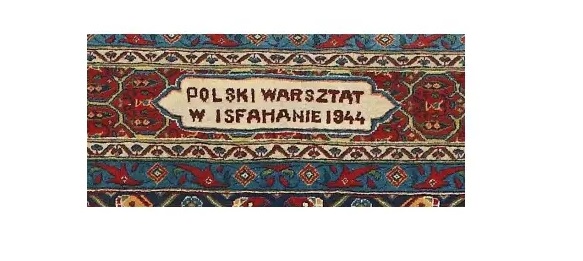

Polish Carpet Workshop in Isfahan 1943-44

At the outbreak of WWII and following the devastating invasion of Poland by the allied forces of Germany and the Soviet Union; many Polish children, predominantly orphaned, found refuge abroad. The Iranian city of Isfahan stands out in this respect as a place of a particular importance.

Thousands of families expelled from their homes in the Soviet Union-annexed eastern Poland were sent onto a forcible exile in Siberia.

Many died in that harsh and most inhospitable part of northern Asia, but many survived and were eventually allowed to leave.

They were unable to return to their country though, instead, they sought refuge outside of the war-torn Europe.

Thousands reached Iran, mostly children, and found sanctuary in Isfahan.

Children who were evacuated to that ancient Iranian city were welcomed with open arms, at least initially; primary, secondary, and vocational schools were set up to accommodate pupils of all ages.

They were taught metal works, tailoring, and other trades, and a small group of girls of 14-and-over years of age, the art of carpet making.

An experienced Persian instructor supervised learning while an Armenian artist Aleksandr Nerssesyan oversaw the various aspect of the design.

Those young girls never found employment with city’s ateliers; they continued their work at the school which later, perhaps informally, became known as the Polish Workshop in Isfahan.

The project was suddenly interrupted, apparently as a result of increasing hostility toward refugees in the face of famine that plagued Iran in winter of 1943.

‘… the initial warm welcome by the country’s population turned bitter the following winter, when, amid low supplies, Polish refugees were seen as “parasites,” and graffiti (/) read, “all of Persia is hungry as it watches the Poles and the British eat its bread.”’ (Tehran Children Mikhal Dekel)

For reasons of safety, all children were relocated abroad; their journey continued. Many moved to Lebanon, Kenya, New Zealand, and later to Britain. Hundreds of Polish Jewish children were sent to then-British-controlled Palestine.

There are four unique Isfahan carpets on a permanent display at the Royal Castle Museum in Warsaw. All four are attributed to the small group of Polish girls from Isfahan. All show an advanced level of skills and save for one are quintessentially Persian in style.

Two exemplify the classic Islamic prayer design. One in an all-over boteh pattern resembles carpets from Sultanabad or Qum; so does the last but it features an image of a white eagle, the Polish national emblem, in the main field. All four bear signatures ‘Polish Workshop in Isfahan.’

The last of the four features the names of the artists: Zofia Cebula, Zofia Wieczorek and sisters Wanda and Jadwiga Igraszek engraved on a brass plaque on its back.

It is believed that two of the four carpets were meant to be gifted to Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt. Both, however, the president of the United States and the Prime Minister of Great Britain were considered to have betrayed the Polish cause at the 1945 Conference of Yalta.

The carpets were sent instead to the headquarters of the Polish government-in- exile at Eaton Place in London.

There was a fifth carpet as well. It was offered to General Wladyslaw Anders, a prominent member of the Polish military elite, ‘our Moses’ as he was referred to by the many survivors of the long journey from gulags of Siberia to Iran and onwards.

Upon his death, the carpet was left in custody at the Polish Institute and Sikorski Museum in London.

There were allegedly a few more carpets, all at one point in London. One was reported lost during renovation works at Eaton Place, others are missing as well.

A note from the author: Despite the support of Władysław Czapski and Irena Godyń , both survivors of the epic journey from the gulags of Siberia to Iran an onwards, the author was unable to establish the destinies of the young talented young girls from The Polish Workshop in Isfahan: the aforementioned Zofia Cebula, Zofia Wieczorek and sisters Wanda and Jadwiga Igraszek as well as Leokadia Kądziołko, Stanisława Leszczyk, Jadwiga Minkler, Marta Pawlus, Leokadia Celińska, Marta Krysińska, Helena Szkuderska, Irena Aulich, Genowefa Czyżyńska, Janina Sowa, and Maria Węgrzyn.

Piotr Wesolowski

Special thanks to Katarzyna Połujan from Pałac Pod Blachą – Muzeum Zamek Królewski w Warszawie

‘It is no great boast, but I believe I was a better hand at worming out a story than either of my fellows (/) …’ (-) Robert Louis Stevenson The Body Snatcher

Ahmad ibn Fadlan, the 10th century Arab explorer spoke of the Byzantine brocaded silks while describing a funeral ceremony of a Volga Viking chief.

For centuries, the Volga served as part of the trade route connecting Scandinavia with the Eastern Roman, and later Byzantine Empires.

There is plenty of evidence to support this thesis; historical records, artefacts: coins, precious metals and gems, textiles.

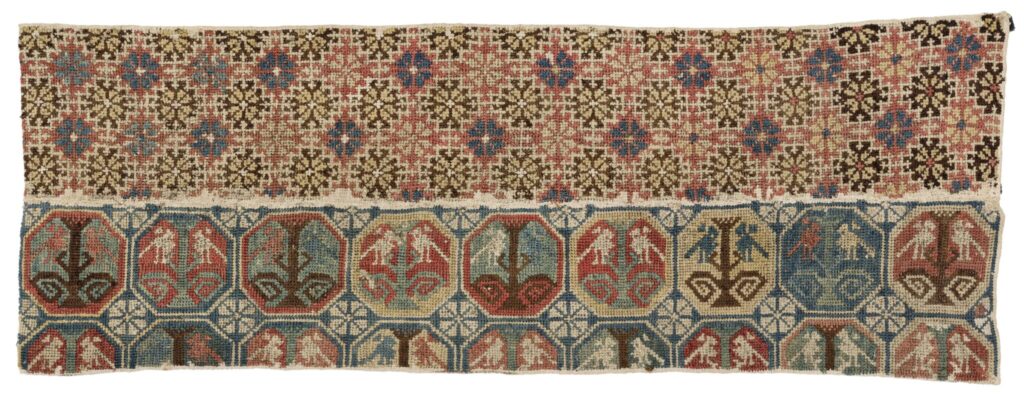

One textile, arguably much later however, attracts more curiosity than those in Viking collections.

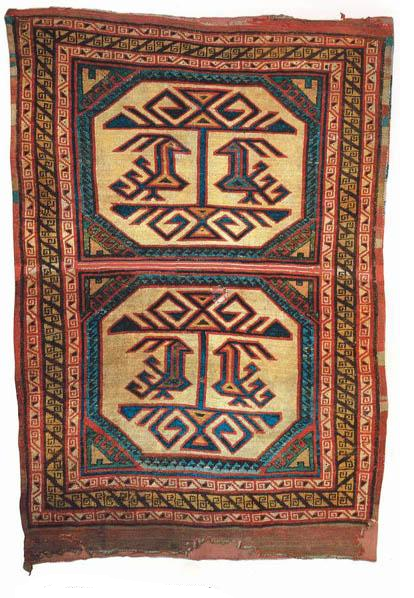

It differs from the Persian and Byzantine silks found in burials across Scandinavia, and it closely resembles rugs seen in Italian Renaissance art, namely in works by Domenico di Bartolo and Bartolomeo degli Erri, and perhaps more importantly, in the world-famous Dragon and Phoenix carpet purchased in Rome by Wilhelm von Bode for the Museum of Islamic Art in Berlin.

Since it was found in a parish church of Marby in Sweden, the iconic 15th century artefact has been a subject of intense scholarship.

It is on display at the National Historical Museum in Stockholm as proof of the very early presence of the so-called ‘Anatolian animal carpets’ in the Baltic regions of northern Europe.

The well-known, albeit notorious independent rug scholar Jack Cassin disputes however the Anatolian origins of the Marby rug.

The well-known, albeit notorious independent rug scholar Jack Cassin disputes the Anatolian origins of the Marby rug. ‘[Cassin] had the opportunity to examine (/) several other now famous early ‘Anatolian’ rugs (-) in the London [at] home/gallery of Lisbet Holmes.’ and he argues that ‘the iconography and some of its physical details don’t appear to place the Marby rug within any of the early groups of these animal rugs and surely do not imply and deeper connection to these fragments’ referring to the classification establish and illustrated in Carpet Fragments by Carl Johan Lamm

He also visited Stockholm where he calims to have ‘had the opportunity to see the Marby rug] at very close range’ .

‘[Cassin] had the opportunity to examine this rug when it was with several other now famous early ‘Anatolian’ rugs (-) in the London home/gallery of Lisbet Holmes.’ and he argues that ‘the iconography and some of its physical details don’t appear to place the Marby rug within any of the early groups of these animal rugs and surely do not imply and deeper connection to these fragments’ referring to the classification established and illustrated in the acclaimed Carpet Fragments by Carl Johan Lamm.

What is more, the Marby 1925 discovery constitutes a rather isolated occurrence as there are no mentions of such rugs in Scandinavian church annals, and none has never been found in the Viking burials.

And yet, ironically, there is an abundance of the rug’s principal motif, a tree flanked by two birds, in some of the oldest examples of Scandinavian textiles.

One such textile is a 16th century jynne, a pillowcase from Ramsele Church in northern Sweden. It is now exhibited at the Nordic Museum in Stockholm.

Another, an 18th century jynne, formerly in late Peter Willborg collection, also features the same motif linking it to the rug discovered at Marby.

Marby Church however lies on a pilgrim’s route to Nidaros Cathedral in Norway, and quite possibly, owing to the exuberant costs of the Ottoman rugs in mediaeval Europe, the original location of the Marby rug.

The northernmost Christian cathedral in the world must have been perceived by the Holy Seat as an important place of worship.

The Vatican dignitaries may have visited the site at a point to offer expensive gifts in exchange for future donations, and possibly the exotic Anatolian carpet as well.

If later displayed at the cathedral, the rug may have engendered enough influence in the region to be copied in folk-art across Scandinavia.

In its history, nearly a millennium long, Nidaros Cathedral suffered many calamities. It was ravaged by fires with its entire archives and inventory records gone up in flames.

It was always rebuilt. It also survived the turmoil of the 16th century Reformation.

It is possible that when the newly established Church of Norway took over the Roman Catholic Church ownership of the cathedral, the Anatolian rug, a cherished possession, was sent for safekeeping to Marby.

It may have remained there ever since; left in a crypt of a church in one of the most desolate parts of the country.

Piotr Wesolowski

Additional reading: ANATOLIAN RUG STUDIES: The Marby Rug: Some Questions Examined by Jack Cassin

BYDENNIS DIMICK

PUBLISHED SEPTEMBER 21, 2015 NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

Try to imagine how life would change if your water supply suddenly vanished.

That’s what happened to the Ma’dan people of southern Iraq—the Marsh Arabs—when the water started to disappear from the Mesopotamian marshes, or “the land between the rivers,” where they had lived for more than 2,000 years.

A slender canoe filled to the rim with reeds in al-Auger village, Central Marshes.

The rivers are the Tigris and Euphrates, and these marshes of the Ma’dan are often said to have been the storied Garden of Eden. The marshes dried up after new upstream dams diverted river flow away from them, and Iraqi President Saddam Hussein drained them as retribution for uprisings against his regime.

The undisturbed life of the Marsh Arabs—who for centuries lived in isolation from outside pressure—was lost. But a unique set of photographs has surfaced that reveals the watery world of the Ma’dan before the effects of development and political upheaval intruded.

Norwegian photographer Tor Eigeland visited these marshes in 1967, and most of his pictures remained unseen until the publication of his 2014 book When All the Lands Were Sea: A Photographic Journey Into the Lives of the Marsh Arabs of Iraq.

Eigeland’s pictures offer a glimpse into this culture before it was destroyed when the water nearly vanished. As droughts and water scarcity increase globally due to climate change and increased demand for limited supplies, it’s useful to remember that without water there is no life.

(Read about a decade-long attempt to reflood the marshes that is faltering for lack of water.)

Tor and I have known each other since we collaborated on the 1982 National Geographic book The Desert Realm. His long career as a photographer and writer included contributions to several National Geographic books and to Traveler magazine. In an email exchange, Tor recalled his trip to the marshes of southern Iraq while that culture still thrived—and what its loss means for us.

DENNIS DIMICK: Tell us about the project in the Iraqi marshes that produced your new book. How did this come about? And what came of the work in the late 1960s, when you first shot it?

TOR EIGELAND: While living in Beirut in 1967 I was asked to go to Iraq to illustrate a chapter of a Time-Life book titled Cradle of Civilization—and a few of the images were published there. The bureaucratic difficulties in getting permission to enter the marshes deserve a whole chapter, but I’ll spare you.

Once there I was so totally fascinated by this watery, ancient world that I stayed on much longer than required. At the time I had no way of knowing how valuable documentation of life in the marshes would prove to be, even the little bit I could contribute.

DENNIS: Can you describe what this area of Iraq between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers was like when you were there?

TOR: As soon as my little boat entered the marshes from terra firma, I felt, quite abruptly, as if I had actually left the real world. There was nothing familiar there. I had entered a mystical domain of canals, small lakes, and forests of tall reeds. The first village I saw at dusk was like no other place I had ever seen.

Built along a sort of channel, dozens of smart canoes with elegantly curved prows were drawn up along the banks. Their houses, called mudhifs, were built from reeds in arched shapes, with decorative patterns that date right back to ancient Babylonia. Darting about were half a dozen small canoes running unknown evening errands. Every aspect of their lives was lived on or near the water.

I had entered an isolated, functioning world little changed for thousands of years. A world that turned out to be one of generous hospitality toward strangers, somewhat like that of the desert Bedouin.

More than anything, I recall a feeling of timelessness, especially at dawn and dusk, when the feeling could be almost trancelike, especially with a camera in hand.

DENNIS: It has been nearly 50 years since you took these pictures. Why publish this book now? Is there a lesson for us?

TOR: We can thank Saddam Hussein, a seriously cruel specimen of mankind, for this book. As a revenge against the Shi’a south of Iraq who rose up against him, he, in his rage, drained the vast marshes, drove the Marsh Arabs out by force, and caused irreparable damage to these enormous, rich wetlands.

Additionally, huge dams in Turkey have further reduced the water flow of these rivers to a point where the marshes can never again be the same despite current brave efforts to reflood them.

Realizing then that I had some unique records of a destroyed, vanished civilization, I knew I had to do this book. A trip like the one described in the book can never be repeated. It is also a tale of how people can live simply in harmony with nature.

DENNIS: After Saddam Hussein was deposed, some people returned in hopes of restoring the drained marshes and reinhabiting their former homes. What has happened?

TOR: Assam Alwash, an engineer who won a Goldman Environmental Prize for his work in the marshes, has worked for years to restore them and has done more to reflood the marshes than anyone else. He wrote me last month about the effects of ongoing drought and the loss of river flows from upstream dams.

He said the situation is dire. The marshes are half what they were six months ago. Some people are comparing today to 1995, when animals began dying due to lack of water. He said the government cannot be bothered with the situation.

Also, vast Turkish dams were built upstream without directly evil intentions but also without real concern for what would happen downriver. This fact alone, in the long run, would have reduced the marshes to a fraction of their former glory.

DENNIS: What reactions have you received so far from the publication of this book?

TOR: Readers have expressed gratitude for my having recorded elements of a practically dead civilization before it was too late, and surprise about the mere existence—and disappearance—of the Marsh Arabs.

This is a classical example [of] how human greed and politics can in no time at all destroy an ancient human civilization and a vast, ecologically sound, and alive paradise. It clarifies this idea that without water there is no life. It’s something to think about very seriously—this could happen anywhere.

Dennis Dimick serves as National Geographic’s executive editor for the environment, and is a long-time picture editor. You can follow him on Twitter, Instagram, and flickr.

Help Children in the High Atlas

Buy any Berber Rug in our collection in the month of February and we will donate 20% of the price paid to provide school children in Amlougui village near Setti Fatma (Ourika valley) with warm clothes.

We will additionally cover global shipping costs

You may also choose to make a small donation directly.

This small charity project is recognised by the Government of the Netherlands

You may want to read this Al Jazeera article

The origin of this design can be traced back to the Phrygian or possibly Hittite civilisations in Anatolia.

The archaic design in this very old Tulu was inspired by the so-called step monuments found in Central Anatolia.

These rock monuments attributed to Phrygian and Hittite civilisation though called ‘thrones’ (e.g. the throne of Cybele, Phrygian Goddess, Mother of the Gods, or throne of Midas) are believed to be altars, or possibly sacrificial altars dating to the Stone Age

Below, the so-called Throne Monument, a Phrygian altar or the throne of Kybele, the Goddess of all Gods, and the inspiration for the archaic ‘ascending arches’ pattern often found in Anatolian rugs

A vertical rendition of the same design, known among the Turkish merchants as ‘bacali’ from the Turkish word ‘baca’ – a chimneystack; evolved likely from the Phrygian tombstones scattered among the ancient ruins of Cappadocia.

to be continued …