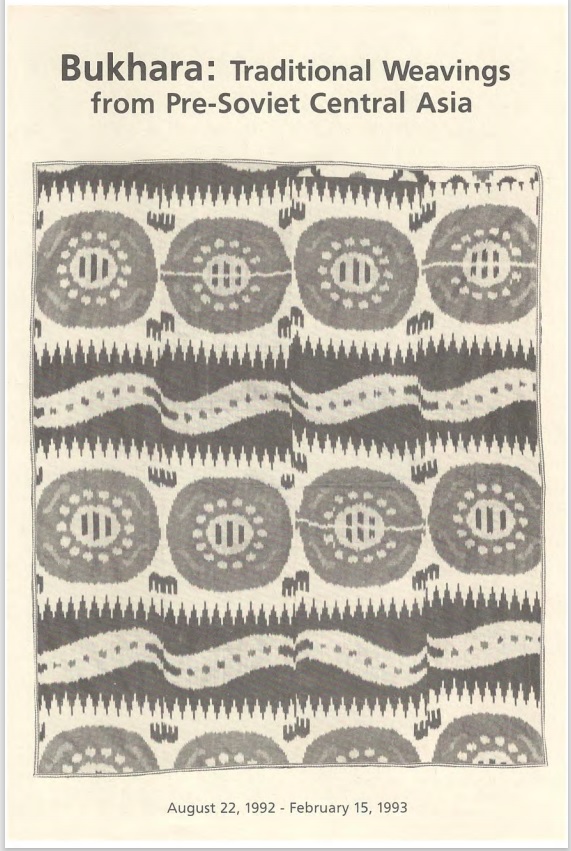

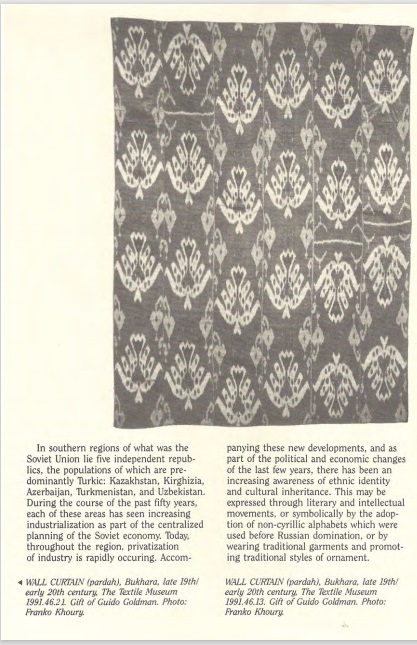

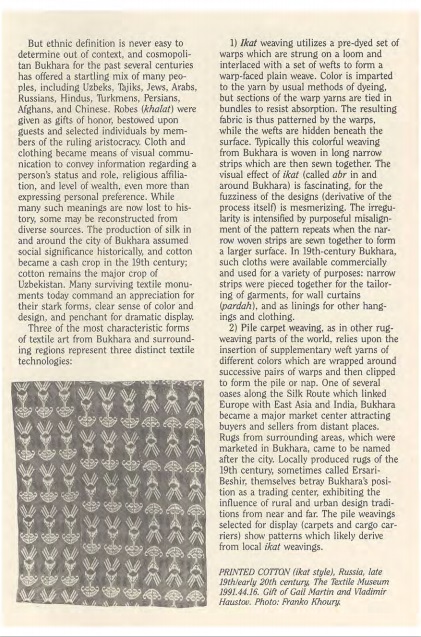

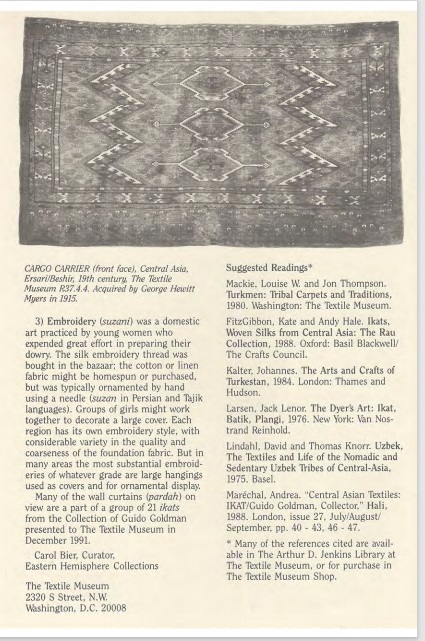

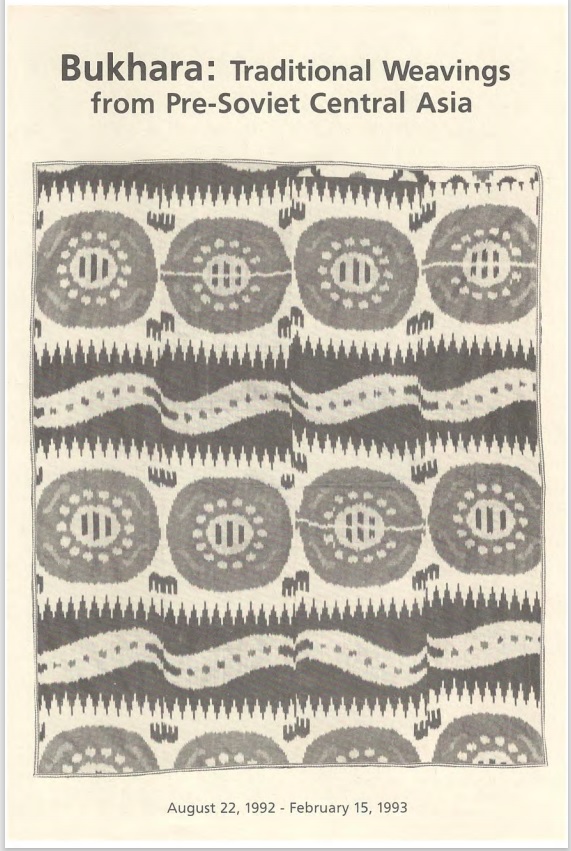

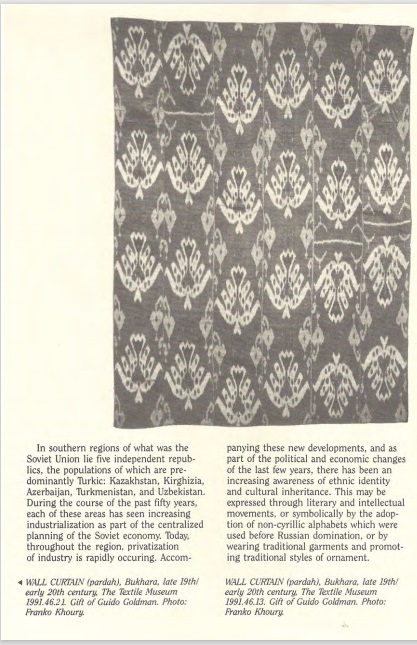

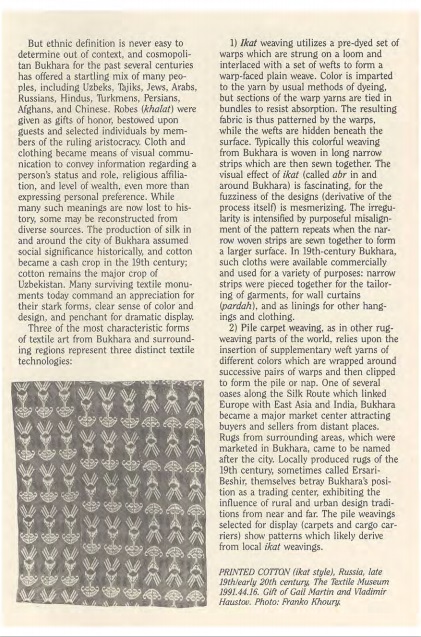

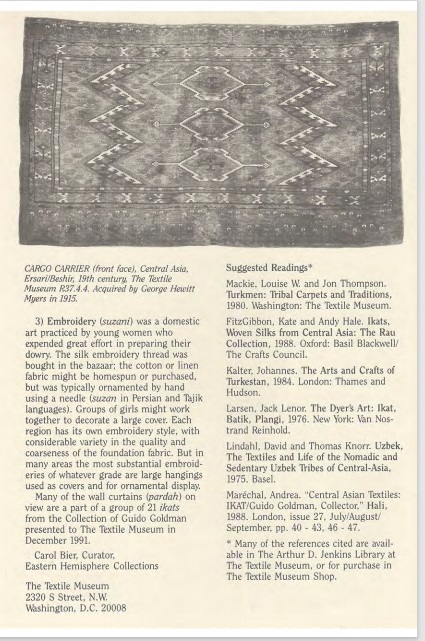

Brochure of an exhibition organized by The Textile Museum, Washington, DC, on view in 1992-1993. Drawn from The Textile Museum collections.

The main aim of this blog is to share the passion for carpet weaving arts around the world. The articles published in this blog have a very generic character with no claims to academic authority.

Brochure of an exhibition organized by The Textile Museum, Washington, DC, on view in 1992-1993. Drawn from The Textile Museum collections.

[From the perspective of collectability, there are] ‘… two [significant] periods in Turkmen history: the era in which most Turkmen practised nomadic pastoralism and were organised according to indigenous structures of affiliation and leadership; and the period following their subjugation by the Russian colonial regime, which is associated with the sedentarisation of nomadic Turkmen and an increasing dependence on the market. (-) Mark Collard

’ The date marking the transition had been established at 1882, the final surrender of the Tekke tribe and the abandonment of Merv, a once thriving metropolis termed by chroniclers as “the mother of the world” .

All pre-1882 Turkoman weavings represent therefore the rarest and most collectible group of artifacts. Conversely, the later 19th and early to mid-20th century works are viewed as mostly decorative.

The period of Turkmen dominance of the Merv Oasis is often referred to as the Classical period, and weavings from that period; classical works.

The common characteristic is the classical Turkmen works can be only established in reference to later pieces which in comparison display busier fields, wider borders, and a finer structure.

‘A predominance of small ornaments in a Turkoman carpet may indicate a later period, as does (…) the ration of the width of the borders to the central field. In classical pieces this proportion is generally between 1:4 and 1:6.’

and ‘… old carpets are significantly more loosely knotted and coarser in structure. As the guls grew smalled and flatter, the knot count incresed and the carpets became ‘finer’.’ (-) Werner Loges Turkoman Tribal Rugs

Therefore, analyses of the technical struture, field ornaments and border motifs in relation to negative space are essential to establish the age and provenance of a given Turkmen textile.

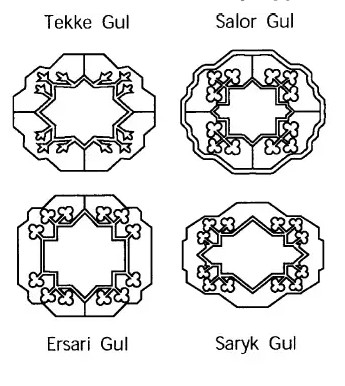

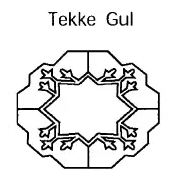

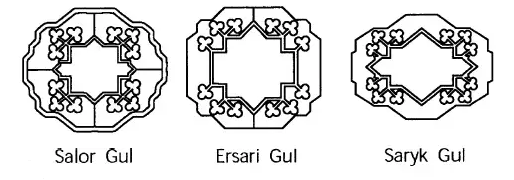

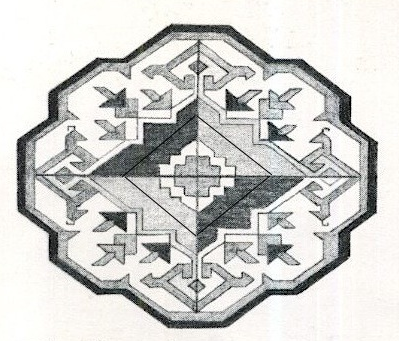

A study of the main carpet ornaments, and the gul in particular, provides evidence of the tribal origin of a given textile.

A gul consists of central ornament and the border; in the field, between the border and central ornament there are projectiles. These appear to ‘darts’ in the Tekke gul (see below),

and ‘clovers’ in in the Salor, Ersari, and Saryk guls (see below).

Furthemore, while the clovers in the Salor gul display a single stem, Ersari and Saryk guls show two.

Prior to the Russian expansion and colonization of Central Asia ‘For centuries the Turkoman people have been bonded together in strongly independent tribal groups. ‘

However, the numerous battles and the final defeat of the Turcoman tribes at Merv (1882) mark the begining of a steady erosion of culture.

The construction of the Trans-Caspian railway encroached on the Turkoman territories forcing many tribes to relocate to Iran and northern Afghanistan.

The Trans-Caspian military railway was inittialy built to facilitate the Russian troops to penetrate Central Asia; armoured trains were a most efficient military means to expand and control newly conquered terrirories. These trains transported troops and later supplies and amunition.

During this period that followed Turkoman women continued to produce various textiles, carpets, chuvals, etc. but not only were those a far cry from the classical period works, they no longer represented, at least not to the same extent, the specific tribal identity.

James Allen, an authority of the subject of Turkman textile arts suggests that ‘The real classical period was before the railroad and when firearms changed to ground rules of their life. The transition period from the bow and arrow horse mounted warrior phase and Turkmen on the run and looking for a place to live their life ‘as well as possible’ was before the Merv Oasis period. This is when the Turkoman weaving arts reached their peak.

The transition, from the production of textiles mainly for domestic use to a more commercial production on a larger scale, Allen argues, was from 1780-1820. This pushes back the prime period of collectable pieces so far that ‘too few pieces exist for the world market’.

A more convenient arbitrary date was established by antiquity merchants to those woven before 1882 (the battle at the Merv Oassis).

At the Merv Oasis, 1847-1882, Turkman rugs were produced in unprecedented quantities and sold to finance the war against Russia.

The Turkmen lost and their traditions started to deteriorate after their defeat. The weaving of the Tekke before 1882 was largely copied from antiques the tribe held; many Merv period pieces have the designs of true classical pieces. They can only by told apart by true schollars (Allen)

This is when the Turkoman weaving arts reached its peak; rugs were produced in unprecedented quantities and sold to finance the war against Russia.

The transition, from the production of textiles solely for domestic use to more commercial production on a large scale, Allen argues, was from 1780-1820 pushing ‘back the prime line of collectable pieces back so far that too few pieces exist for the world market’. A more convenient arbitrary date was established by antiquity merchants to 1882 (the battle at Merv Oassis.)

A.G.

This short documentary offers a glimpse into the life of pastoral peoples of the Iranian Zagros Mountains. It is available only in the original language.

Images however speak for themselves.

Enjoy watching click here

Thare are more … Please inquire

Carol Bier, Research Associate

Brochure of an exhibition organized by The Textile Museum, Washington, DC, on view 28 March – 7 September 2003.

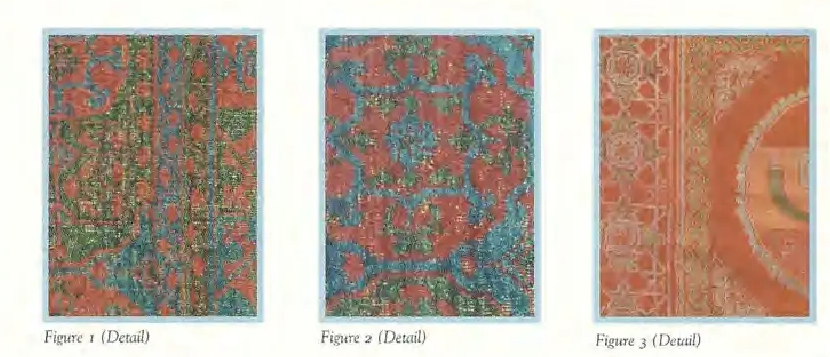

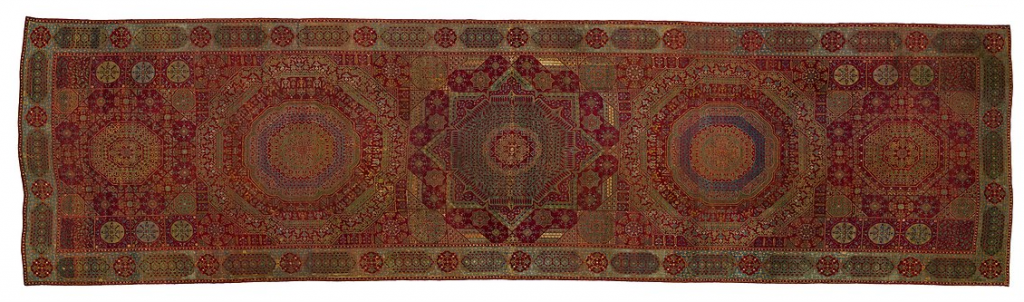

Mamluk rugs are considered by many to be among the most beautiful of any rugs ever created. The brilliant reds, greens, and blues (figs. 1 and 2) are reminiscent of rubies, emeralds and sapphires; whether this was an intentional evocation is not known.

But The Textile Museum’s holdings of Mamluk rugs, unparalleled in the world, are truly the “jewels” of the collection. Simply by virtue of the fact that they date from the late 15th century, Mamluk rugs comprise one of the most significant groups of classical carpets.

Their lustrous wool and wondrous color, as well as their geometric designs and careful execution, contribute to the characteristics of a cohesive group from the points of view of design, structure, materials, color, and layout.

Yet, this is also a group for which many questions remain unanswered. The emergence of this unique group rests upon no known development of rug weaving traditions. Nor is the influence of the three-color geometric patterns of Mamluk rugs felt in later traditions.

In contrast, the weave structure of Mamluk carpets is retained in Cairene carpets manufactured immediately after the Ottoman conquest of Egypt in 1517, which share technical characteristics, while reflecting newly emergent Ottoman floral styles.

Despite such uncertainties of origin and early development, Mamluk rugs show an exceptionally high degree of uniformity, more so perhaps than in any other group of rugs prior to industrialization and mechanized production.

Two rugs in the exhibition (figs. 1 and 2) demonstrate consistency of dimension, color, structure and layout, the proportions of which are determined geometrically.

Larger rugs also show a proportion based on geometry of the circle and the square. Mamluk rugs of the three-color variety (red, blue, green), as well as those with four, five and six colors (the primary three plus white, yellow and brown) also demonstrate similarities of design and layout, as well as consistency in weave structure and yam preparation.

The warps are depressed, which makes identification of the knot formation difficult (symmetrical and asymmetrical knots on depressed warps appear identical on visual analysis without actual penetration of the fabric).

The most frequently encountered knot count is 11H x 11 V, ranging from 100-130 knots/square inch, with a fairly consistent count of 22 warps/inch and 22 wefts/inch. This regularity in knot density in the proportion 1: 1, horizontal to vertical, makes for even-sided polygons such as squares and octagons, as well as circles and right isosceles triangles of uniform dimension.

There are two types of octograms (eight-pointed stars), both of which play with the geometry of the square within a circle. The warps, wool, are composed of four strands, S-spun and Z-plied; most warp sets are dyed green, sometimes arranged in groups forming stripes.

Wefts are often dyed red or pink, and may be two or three shoots. While all of the pile colors usually show a fair amount of wear, areas of brown pile shows extensive loss, which is probably the result of a high iron content in the dyebath, either as mordant or dyestuff.

We do not know where the Egyptian rug-weavers may have obtained the lustrous wool for these carpets; the quality of yhe wool is distinctly different from that Figure 1 Figure 2 Figure 3 which appears in Coptic textiles of an earlier age, or garments from the Fayyum where sheep-rearing has a long history.

We do not know who might have designed the unique geometric repertory of Mamluk rugs, although it is likely that such designs were developed in court ateliers that were also involved in preparation of designs for architectural ornament and the illumination of Qur’ans, for which there are numerous parallels to rug patterns.

Yet, there are also elements in Mamluk rug design that find no ready parallels among the traditions evident in arts of the book, other objects, or architectural decoration. In particular, the umbrella like leaf appears to be unique to rug-weaving, where it is combined in groups of three and five to form clusters, or repeated to form scrolling vines that define both borders and backgrounds.

The red color is also unusual in comparison to other rug-weaving traditions; the dyestuff lac has been proposed, which would presumably have been imported from India.

We do not know why the warps were dyed green, or even where these carpets were actually woven. To judge from the quality of craftsmanship, as well as the consistency of geometric patterns in relation to the monuments created under the patronage of the Mamluk Sultan Qaitbay 0468-96 ), it seems reason able to accept the attribution of these carpets to his reign in the final quarter of the 15th century, and the assumption that they were likely woven in Cairo under supervision by the court.

An unusual carpet, known from many fragments in two Florentine museums, and one large fragment at The Textile Museum (fig. 3) contributes further to the complexities associated with understanding Mamluk carpets.

Four of the fragments bear the composite blazon of office of an amir, clearly establishing a link to the court of Qaitbay. Yet the carpet’s technical characteristics, which include its knot count (7H x 7V) and long pile, its colors, as well as its rich repertory of geometric compositions, are distinct from the cohesive design group that we accept as Mamluk by attribution.

With major questions concerning who wove these carpets, under what conditions, and for whose use, this is a clearly an important rug tradition about which much is yet to be learned.

Other signifact Mamluk rugs:

More about Simonetti Mamluk carpet … (click)

A.G.

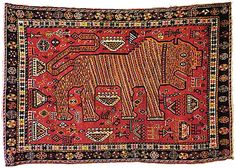

Tribal rugs from Iran’s Zagros Mountains have for decades captivated the attention of rug collectors the world over.

At auctions, the tribal works by the Qashqai, Bahtiari and Afshars would at times outsold exquisite artifacts from the most prestigious palace workshops.

The charm of these primitive works of art in textile rests mainly in their fascinating play of colours, and their spontaneity of design.

Among these tribal wonders, a coarsely woven, long-pile and low-knot density gabbeh plays a very important role.

Efforts by rug collectors and educators such as Jim Opie and late Peter Wilborg led to increased popularity of gabbehs (Bahtiari Kersaks) bringing this ancient ‘uncomplicated’ art out of the ‘black tents’ to the world museums, and the market at large.

‘The increased interest in gabbas among Western collectors since the 1980s and a shared aesthetic with minimalism and the color field movement in modern art, as well as a contemporary appreciation of the charm of gabba rugs, have led to higher demand [and] has spawned commercial manufacture …’ (Jean-Pierre Digard and Carol Bier)

The first references to gabbeh can be traced in texts dating to the middle of the 16th century (J. Opie), however:

‘Some authors believe that gabba represent much older traditions of pile weaving, and that their origins may date to the emergence of this technique in the steppes of Central Asia soon after domestication of sheep.’

(J-P. Digard and C. Bier)

This thesis is strongly argued against by J. Opie:

‘… [there is] abundant evidence of extremely old tribal design traditions in western Asia, especially in Iran, [suggesting that e.g.] Luri gabbehs, like indigenous Luri weavings did not merely survive in southwest Iran, but originated there, and that the weaving techniques involved were even more deeply rooted in western Asia than they were, out on the steppes.’

Sadly however,

‘Those that have survived date only from the last two centuries. There is evidence, however, that the lion motif was utilized by rug weavers prior to this.’ (Tanavoli)

These gabbehs, insinsts Opie, originated in Luristan taking root later further north among the Kurdish tribes as far as Sanandaj, Nehavand, Bijar and south among the Qashqai (also Tanavoli, Amanolahi)

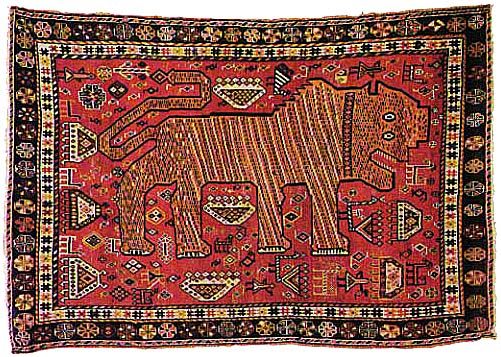

An interesting element common to gabbeh are the various representations of anthropo- and zoomorphic motifs. A gabbeh that stand out in this respect is the so-called gabbeh-ye siri, the lion gabbeh.

The technical structure of the lion gabbehs – a higher knot-count, lower pile – may suggest their greater relevance among the nomads alluding perhaps to some very distant shamanic past.

‘Lion guards the tent’ (Opie); a tent represents a family.

Lions represented in the earliest style of gabbeh-ye siri, do not however feature a lion as we know it. The African lion, it is believed, begins to appear in much later works. It was introduced to Iran through images on imported objects during the Kajar period.

Lions featured in the pre-Kajar gabbehs (circulating in much later replicas and only known to us as such) are representations of a mythical creature symbolizing majesty and masculine power rather than a long extinct Asiatic lion as it is often suggested.

Bazaars in Iran are inundated with commercial replicas of lion gabbeh; they are extremely popular with visitors from abroad.

This is in part at least owed to the extraordinary success of the Iranian artist and avid rug collector Parvez Tanavoli, who views those ‘primitive’ works as a genuine expression of artistic traditions rooted in mankind’s long-forgotten mythologies.

Tanavoli,’s art remains profoundly inspired by the gabbeh imagery, colour and obscure symbolism.

Tanavoli,’s art gained the artist his world-fame and recognition while bringing the spotlight onto that very ancient and genuine artform.

A.G.

Read more about Pavez Tanavoli in our next newsletter

From “Lion Rugs; The Lion in Art and Culture of Iran” by Parviz Tanavoli

(Trans Book, New York, 1985).

My first lion rug

I found my first lion rug in early 1970. Its unusual pattern set it apart from all other Iranian rugs and so captivated me that I bought it without any hesitation whatsoever.

A week or two later another lion rug, different from the first, came into my hands,and then a third. The discovery of these rugs was so exciting to me that I thoughtabout them constantly. I myself knew nothing about rugs like these, nor did those from whom I had purchased them, except for the fact that they were called gabbeh-ye shiri (“lion rug”) in Persian. This lack of knowledge and the utter fascination these rugs held for me led me to pursue them far and wide.

The first of many trips I made in quest of lion rugs was to Shiraz, which is about atwelve-hour bus ride from my home in Tehran. In Shiraz, I found more examples.

For several years thereafter, my life was spent traveling back and forth between Tehran and Shiraz, visiting bazaars on the way, and scouring the mountains and plains of Fars Province for the makers of these rugs.

Two things drove me on. The first was the knowledge that many of these rugs werestill in constant use among their creators and, if not preserved in time, would be completely worn out and discarded. The second was the variety of these rugs.

Almost every day I would find a new lion and the prospect of yet another caused one to imagine a thousand possible patterns and color combinations. In many instances, these reveries were not far from the truth. Those were exciting days. Rug connoisseurs and merchants advised me not to buy such coarse weavings, or at least to buy less frequently so as to not to drive the prices up. The tribesmen were somewhat embarrassed and apologetic that the lions of the rugs were not naturalistic representations of real lions. Yet they were happy that someone would be so interested in their art.

Symbol of majesty and power

Many secrets lie behind the enchanting patterns of the lion rugs of Iran.

The unusual subject matter and composition that distinguish these form other traditional rugs require some explanation, especially since they do not seem to have been chosen solely to please the eye.

Lion rugs, symbols of the tribal bravery, were objects of every day use in the dwellings of their creators. For this reason, many of them wore out and in time were discarded. Those that have survived date only from the last two centuries. There is evidence, however, that the lion motif was utilized by rug weavers prior to this.

The close relationship that these rugs have with stone lions and other objects which bear the image of this animal leave no doubt that the lion motif played an important role in the culture, religion, and nationalistic sentiments of the Iranian people.

Indeed, in the course of the Iranian history, no other symbol has been so long-lived or meaningful. Bravery, patience, generosity, manliness, nobility, and purity are all qualities Iranian have associated with the lion.

The importance of the lion in ancient Iran was such that Iran was called “the land of lions.” In Zoroastrianism, the ancient religion of Iran in which elements — water, fire, and earth — were accorded great respect, the lion was identified with fire. During the achamenid and Sasanid periods, the lion was the symbol of majesty and power, and, with the coming of Islam to Iran, the lion motif continued to play a role in the decorative arts.

The lion motif took on a renewed significance in Iran with the establishment of the Safavid dynasty in 1501.

In the framework of Twelver Shi’ism, the official religion of the Safavids, Ali Ibn Abi Talib, the Fourth Caliph, and First Imam, and leading figure of the sect was known as the “Lion of God.”

This revived use of the lion motif brought only a chance in the form and not in the content of the lion symbolism, for Iranians, from their long experience with invaders and foreign rulers, have always been able to adapt themselves to changed circumstances without losing sight of the original import of their symbols.

In time the lion also came to be the official emblem of the Iranian state and the symbol of the nation.

Subject matter

Most questions people ask about the lion rugs concern the subject matter: Why did the weavers of these rugs choose the lion and not other animals like the horse, camel, or goat?

Without the cultural context described in this introduction an answer to this question would be difficult; all one could say would be “it is due to their appreciation of bravery and prowess” or “it is for the protection of their tents.”

However, if the question is “why were lion rugs woven mostly by tribesmen, especially those of Fars?”, very specific answers can be found.

It would not be an exaggeration to say that in the opinion of the tribesmen of Iran the most important characteristics of a man are courage and virility. The opposite of these traits, fear cowardice, are considered so vile that their attribution to a person can discredit an entire family or tribe.

Life in the mountains and plains and its attendant struggle with heat, cold and wild animals have taught these people the art of survival.

For them the lion symbolizes bravery and prowess. Thus many tribesmen have names which include the Persian word shir (lion) such as Shir Ali or Alishir, Shirzad, Shirdel, and Shir Mohammad.

Others have names like Arsalan or Aslan, which mean “lion” in Turkish. Still othersare known as Asad, “lion” in Arabic. They often tell wonderful stories of how their fathers and grandfathers hunted lions.

As to why most lions rugs were woven in Fars, we must first say a few words about the geographical setting of this region and the existence of lions there, something that without doubt had an influence on the prevalence of this type of rug.

Because of its special natural setting which includes numerous thickets and large game such as wild boar, mountain goats and rams, Fars Province provided an ideal environment for the lion.

For centuries this province was known for its lions, and various beliefs and customs concerning the lion flourished there.

In the 12th century Fars names of areas in Fars such as districts as Kamfiruz and the Arzhan Plain are called “lion mines.”

Many references to the lion hunting expeditions of the Iranian shahs and local rulers of Fars are made in literary texts and poetry of the Islamic period down to and including the Qajar period (1779-1924).

Exactly how long the lion existed in Fars is a matter of considerable interest. According to the Iranian Department of Environment, the last lions were seen in Fars at the beginning of this century while the last lion in Khuzestan was seen near Dezful in 1942. The extinction of the lion in southwestern Iran was simultaneous with the end of traditions of carving lions in stone and weaving their images in rugs. The oldest surviving lion rugs date only from the last two centuries.

Recomended redaing “Lion Rugs; The Lion in Art and Culture of Iran” by Parviz Tanavoli (Trans Book, New York, 1985)

2000, Encyclopaedia Iranica

GABBA (gava in Kurdish and Lori, Īzadpanāh, s.v.; ḵersak in Baḵtīārī, Digard, pp. 128-31), a hand-woven pile rug of coarse quality and medium size (90 x 150 cm or larger) characterized by an abstract design that relies upon open fields of color and a playfulness with geometry. This kind of rug is common among the tribes of the Zagros (Kurdish, Lori-speaking ethnic groups, Qašqāʾīs). The first known reference to gabba is found in a farmān by Shah Ṭahmāsp (r. 930-84/1524-76) dating to the middle of the 16th century (Opie, 1992, p. 124).

Gabbas were said to have originated in Lorestān (mainly from the Ḵorramābād, Borūjerd, and Alīgūdarz regions), whence its use and production spread northward among the Kurds as far as Sanandaj, Nehāvand, Bījār, Kabūdarāhang, and southward in Fārs among the Qašqāʾīs (Tanāvolī, 1977; Tanavoli and Amanolahi; Opie) and as far as Šūl, a village on the edge of the Bušehr province which was reputed to produce the best gabbas. Typically, there is minimal pattern with an occasional stick figure or simply stylized animals on a gabba.

With the exception of the old gabba-ye šīrī, representing a lion, of the Darrašūrī tribe (q.v.; Tanāvolī, 1983), the traditional tribal gabbas are loose and coarsely woven. They have long pile, low knot density, and many rows of weft between each row of knots.

The knotting can be either symmetrical or asymmetrical. Colors derive from undyed wool, šīrī (cream), šotorī (light brown), and sīāh (black, in small quantity, in the form of small flower motifs), from natural dyestuffs derived from plant materials gathered by women and children. Dyed colors show subtle variations that result from the dye-bath and methods used to impart color to the wool yarns prior to weaving. The essential features of the gabba are its small size and soft texture, its comfort (thickness of the pile), and its natural colors.

A gabba is basically the rug of a single person, usually a woman (Digard, p. 174), who carries in it from place to place her hearth, mašk (goatskin sack for carrying water), loom, cradle, etc.; sometimes a fur rug (taḵt-e pūst) or a felt rug (namad, see FELT) performs the same function. A gabba may also be taken to the ḥammām as a mat or used to cover the back of a mount instead of a saddle.

Traditionally, gabbas were woven for local domestic use, not for sale. In particular, the long pile and floppy handle made them useful as sleeping blankets.

The increased interest in gabbas among Western collectors since the 1980s and a shared aesthetic with minimalism and the color field movement in modern art, as well as a contemporary appreciation of the charm of gabba rugs, have led to higher demand which has spawned commercial manufacture in India and elsewhere, often using synthetic dyes, for the home-furnishing markets in Europe and the United States.

In Persia, the weavers of some tribes (especially among the Qašqāʾīs) have been working exclusively for foreign markets. Demands of merchants who look for new motifs, and the fact that gabba designs were little developed and elaborated, caused the weavers to take liberties with their models and make bold improvisations (Opie, passim).

In the same manner as, or at least to the same extent as, the rugs made at the end of the 19th century did (Helfgott), gabbas offer a significant example of traditional production in which foreign demand has rekindled interest resulting in radical design and functional transformations, while rejuvenating a pre-capitalist sector of the Persian economy.

A further impetus was given to the fashion for gabbas with the appearance of Moḥsen Maḵmalbāf’s film Gabbeh (1996). The rug appears as a recurrent symbolic motif, celebrating life and color against the morbid forces of darkness and explores both the transience and effervescence of life by focusing on a tribal girl named Gabbeh. The film is imbued with a lyrical romanticism far removed from the everyday realities of tribal life.

It is mainly recent collectors and dealers in Germany and Italy who have taken the lead in providing information about gabba. Very few works, either on carpets (e.g., Eagleton) or the tribes (e.g., Beck; Mortensen), mention gabba, and the subject has not received critical scrutiny in academic circles. This is because gabbas, like all tribal rugs (Helfgott, pp. 161-72), were long considered, in the tribes as well as in international trade, to be too coarse to be offered for sale.

Moreover, works that make passing reference to gabba too often erroneously attribute to it uses that it does not have or misleadingly label as gabbas what are in fact large carpets with elaborated motifs (a Lor carpet of 137 by 206 cm, a Baḵtīārī of 104 by 413 cm, and two Qašqāʾī of 152 by 224 cm and 124 by 264 cm in Opie; a Baḵtīārī of more than four meters in Sadighi and Hawkes).

Most extant gabbas date from well into the 20th century, but early dates of acquisition of gabba in The Textile Museum’s collections in Washington suggest 19th century dating for some examples. Some authors believe that gabba represent much older traditions of pile weaving, and that their origins may date to the emergence of this technique in the steppes of Central Asia soon after domestication of sheep.

PLATE I. Gabba, southwestern Persia(?), 19th century. Wool pile on wool warp and weft. 208.5 × 129.5 cm. The Textile Museum R33.00.4. Acquired by George Hewitt Myers.

PLATE II. Gabbas on display at a Qašqāʾī tent in the garmsīr (q.v.). After M. Aḥmadī and M. Maḵmalbāf, Gabba: fīlm-nāma wa ʿaks, Tehran, 1375 Š./1996.

PLATE III. A gabba in a contemporary style. After M. Aḥmadī and M. Maḵmalbāf, Gabba: fīlm-nāma wa ʿaks, Tehran, 1375 Š./1996.

Bibliography:

L. Beck, Nomad: A Year in the Life of a Qashqaʾi Tribesman in Iran, London, 1991.

R. D. Biggs, ed., Discoveries from Kurdish Looms, Seattle, 1983.

G. D. Bornet, Gabbeh: The Georges D. Bornet Collection III, Baar, Switzerland, 1995.

A. De Franchis and J. T. Wertime, Lori and Bakhtiyari Flatweaves, Tehran, 1976.

J.-P. Digard, Techniques des nomades Baxtyâri d’Iran, Cambridge and Paris, 1981.

W. Eagleton, An Introduction to Kurdish Rugs and Other Weavings, New York, 1988.

M.-R. Ḥasanbeygī, “Gabba,” Faṣl-nāma-ye ʿašāyerī, no. 6, 1367 Š./1988, pp. 121-26.

L. M. Helfgott, Ties that Bind: A Social History of the Iranian Carpet, Washington and London, 1994.

Ḥ. Īzadpanāh, Farhang-e lorī, Tehran, 1343 Š./1964.

D. W. Martin, “The Gabbehs of Fars: An Abstract Tribal Art,” Hali 5/4, 1983, pp. 462-73.

I. D. Mortensen, Nomads of Luristan: History, Material Culture, and Pastoralism in Western Iran, Copenhagen, 1993.

Museo nazionale della montagna “Duca degli Abruzzi,” I Gabbeh: un’arte tribale astratta tappeti del Sud-Ovest persiano, catalogue of an exhibition, 14 May-26 June, 1988, Cahiers Museomontagna 58, Turin, 1988.

I. C. Neff and C. V. Maggs, Dictionary of Oriental Rugs, London and Johannesburg, 1977

J. Opie, Tribal Rugs of Southern Persia, Portland, Ore., 1985.

S. Parhām and S. Āzādī, Dastbāfhā-ye ʿašāyerī-e wa rūstāʾī-e Fārs, Tehran, 1365 Š./1986.

H. Reinisch, Gabbeh: The Georges D. Bornet Collection I, Catalogue of an Exhibition at the Graz Kunstlerhaus, 4 April to 20 April 1986, Graz and London, 1986.

T. Sabahi, Splendeurs des tapis d’Orient, Paris, 1987.

H. Sadighi and K. Hawkes, Gabbehs: Stammesteppiche der Bergnomaden am Zagros, Berlin, 1991.

A. Sette, T. Meglioranzi, and L. Zoccatelli, Gabbeh: Tappeti tribali della Persia meridionale, Verona, 1988.

P. F. Stone, The Oriental Rug Lexicon, Seattle, 1996, p. 83.

P. Tanāvolī, Qālīča-ye šīrī-e Fārs, Tehran, 2536 (1356) Š./1977.

Idem, “Gabbeh,” Hali 5/4, 1983, pp. 474-76.

P. Tanavoli and S. Amanolahi, Gabbe: The George D. Bornet Collection II, Baar, Switzerland, 1991.

J. Wertime, “The Names, Types, and Functions of Nomadic Weaving in Iran,” in A. N. Landreau, ed., Yoruk: The Nomadic Weaving Tradition of the Middle East, Pittsburgh, 1978, pp. 23-26.

(Jean-Pierre Digard and Carol Bier)

Originally Published: December 15, 2000

Last Updated: February 2, 2012

Out of all Caucasian rug schools. Kazak seems to be the most varied and stretching across various ethnic groups.

That is not to say that other schools a more ethnically homogenous but the Kazak school of Caucasian rugs includes works by Georgian and Armenian Christians and Azeri Turkic Muslims spanning the territories of 3 present-day countries, formerly Soviet republics.

It is perhaps, and this is an invitation to a group discussion, it is because while other groups are easier to categorize as they share similarities in structure, design and material, Kazaks are those Caucasian rugs that somehow elude classification and, incidentally, constitute the most interesting Caucasian textile artifacts group.

A.G.

The Luri are a nomadic tribe of shepherds inhabiting the valleys of the Zagros Mountains in south-western Iran, a large area they share with other pastoral tribes.

Enjoy a short early 20th century Pathḕ documentary Women of Persia depicting the life of that ancient nomadic tribe.

Thank you for watching

A.G,