“Nain Carpets – a touch of silk for good measure”

Nain is a city in Isfahan Province in central Iran. Up until the beginning of the 20th century, Nain was little known as a carpet producing area. Carpets produced in Nain were labelled as Isfahan; they were predominantly lower grade products sold on the local market.

Then came the unexpected change: a visionary man named Fatoallah Habibian started producing very fine, beautifully designed, quality carpets in wool with finishes in silk. They were all signed Habibian and marked as Nain carpets.

Habibian carpets had quickly become noticed and gained international recognition. Orders began to flow from all over the world while the production within the small studio was limited.

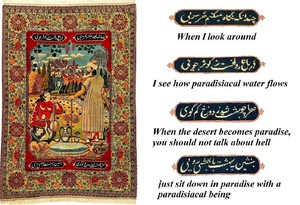

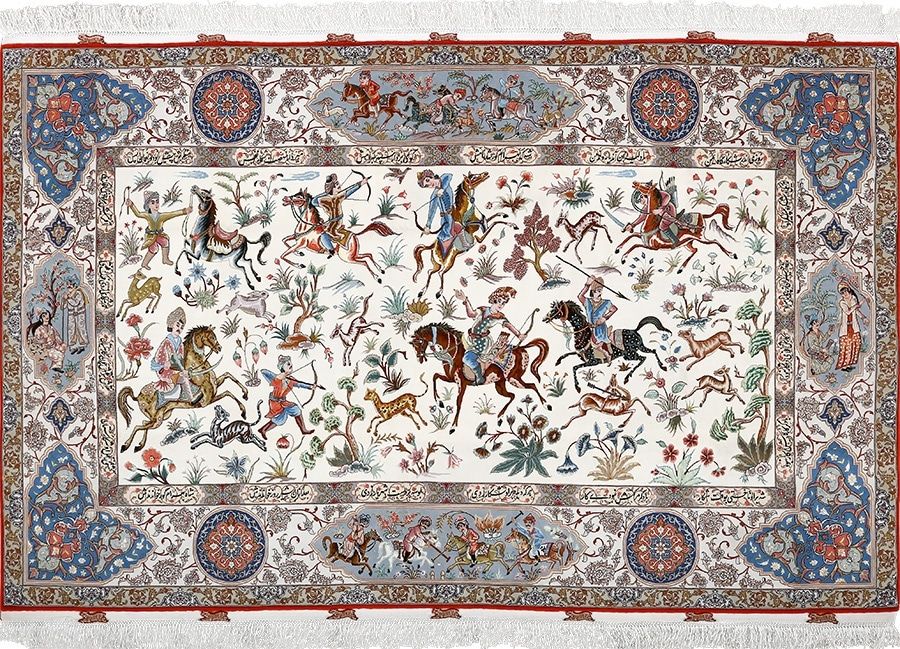

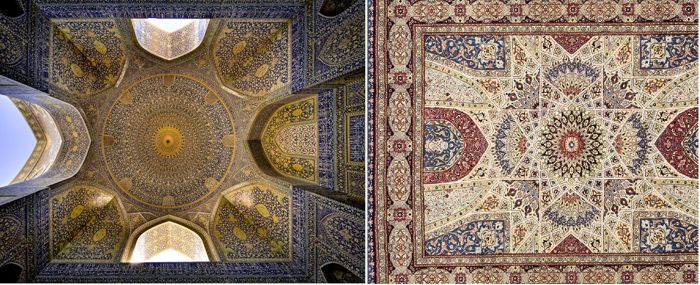

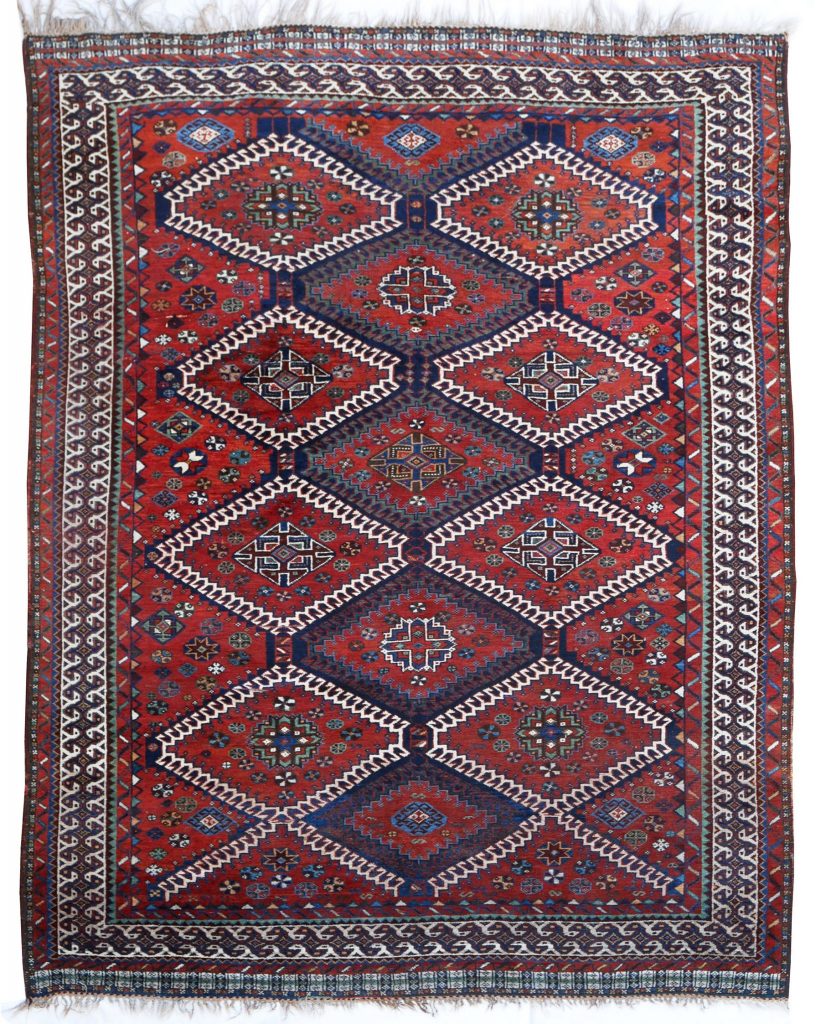

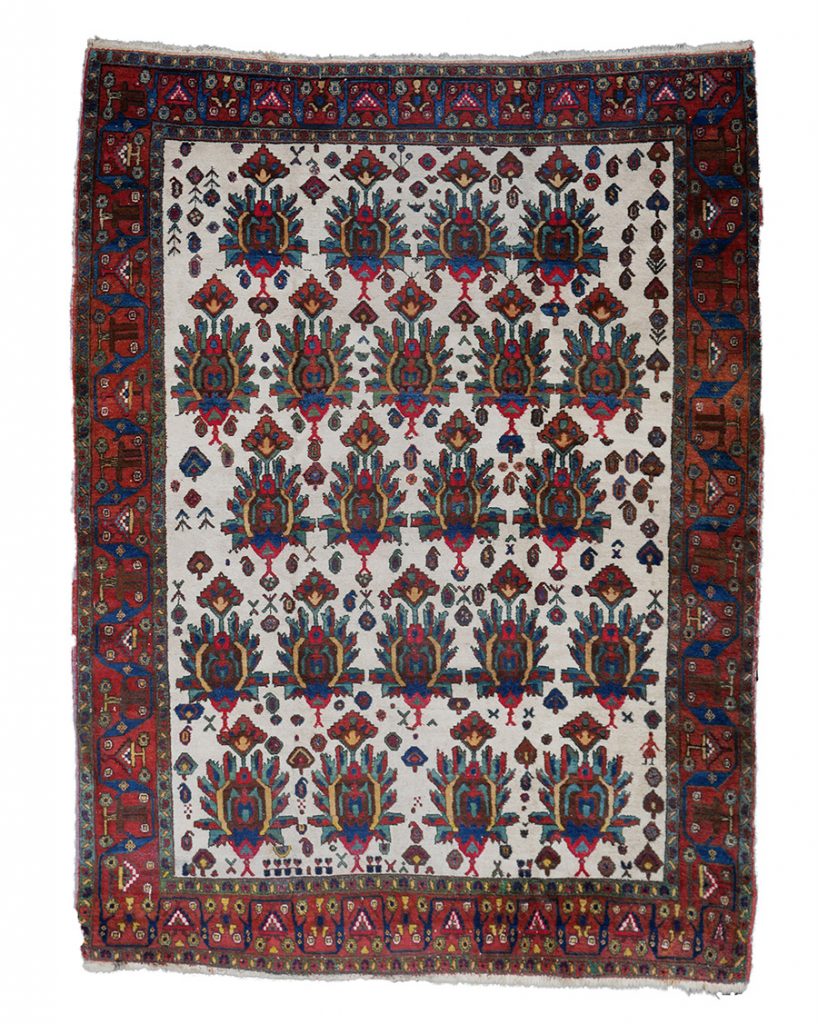

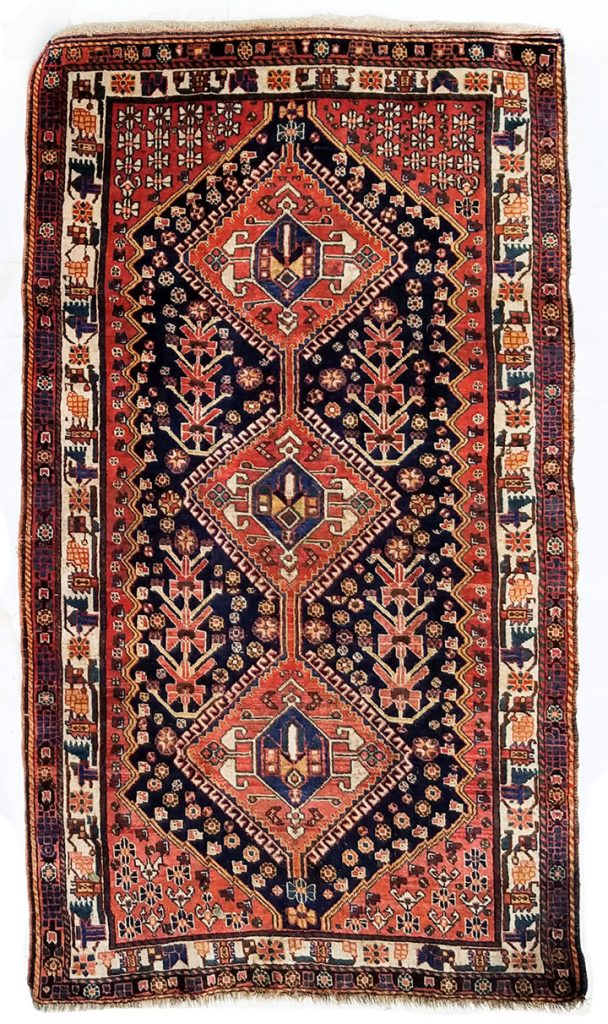

Soon, other manufacturers, small studios in Nain and the area, followed affording a steady supply of carpets in unique and characteristic patterns and a rather limited colour range: grey and blue arabesque designs with a large, centrally located floral medallion set against a warm cream-colored field.

Nain carpets are relatively easy to recognize; nearly all are made within the same style and colour, although red maybe be sporadically used in contrast to the traditional blue.

Almost all Nain carpets have some silk woven into the wool pile. The aim is to highlight the intricate arabesque patterns.

Fatoalah Habbian died in 1975; his studio however never shut down. Beautiful carpets of the highest quality continue to emerge out of his original shop produced under a very strict supervision of the master’s progeny.

All original Habibian designs had been copied by other manufacturers in Nain and beyond; sadly, at times, inclusive of the master’s signature.

Buying a genuine Habibian has therefore become a problem, as ‘fakes’ are aplenty while certificates may be forged as well.

Studying the signature maybe of help to some learned collectors but a chance of paying a high price for a forgery remains a probability.

This situation has seriously hampered the popularity of Habibian carpets; they are however recognizable by their outstanding quality.

‘You will tell a Habibian once you see it’, said once a respected New York merchant.

In essence, buying a Habibian is no different than buying diamonds: always consult an expert.

Here are some tips for buyers on Nain rugs:

LA is a mark of quality in Nain rugs. LA refers to a numberof plies making a single weft thread.

There are 3 types of Nain rugs: commercial quality 9LA ; good to very good quality 6LA; and 4LA carpets wherein a weft consists of 4 plies to a single thread.

4LA Nain carpets with knot densities in the upwards of 1 million knots per square meter are extremely rare.

Importantly, all Nain carpets represent good value and are aesthetically pleasing .

A.G.