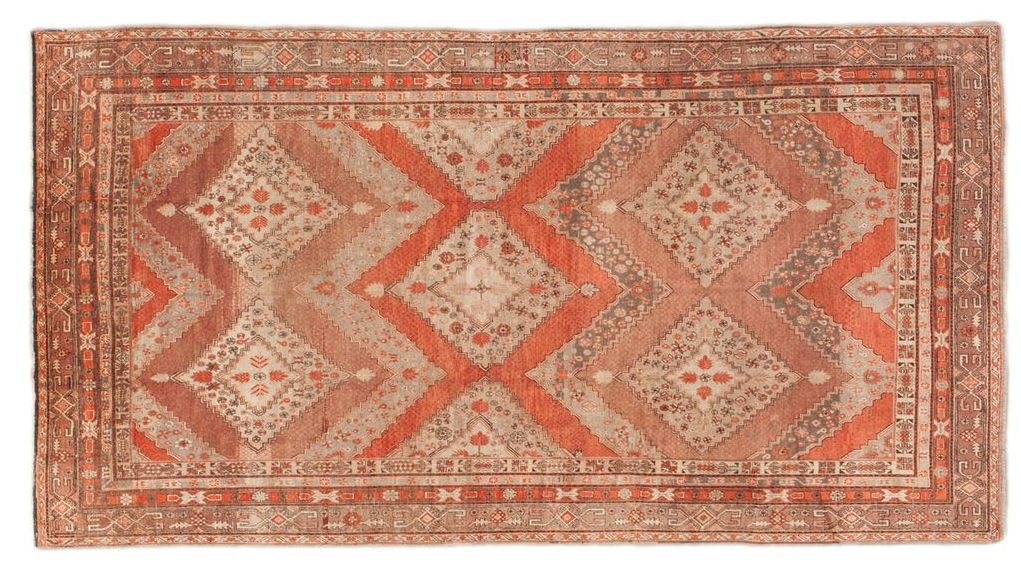

Caucasian rugs are undeniably the most popular among collectors

around the world.

Their charm rests in the spontaneous imagery, colour harmony, format and

relative affordability.

There is however another factor that determines their desirability: they are no

longer made.

When discussing Caucasian rugs, we refer to a specific period in history known as the Renaissance of the Caucasian rug industry, a period that lasted from the second half of the 19th through the first quarter of the 20th century.

‘Caucasian rugs are so interesting because so many designs were used in such a small geographic area over a relatively short period of time.’

(-) Tschebull

In their works, most scholars focus on the period 1880-1920 as a definite beginning and the end of the Caucasian cottage rug industry that produced some of the most remarkable works of village art in textile.

‘The universally accepted name of Caucasian rugsand carpets integrates pieces produced for the most part during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries …’ (-) David Tsitsishvili

There is howver little (confirmed) evidence of rug production in the Caucasus prior to 1880, and rugs made after 1920 are largely poor imitations of their splendid predecessors.

According to Kerimov, the prolonged period of warfare; the long Perso-Ottoman war and later the Russo-Persian war brough distraction and lasting penury to the region that crippled all economic activities.

For many years, the Caucasus was a remote, isolated mountain

region cut off from the world.

Roads and eventually the Transcaucasia Railway were built in

the Caucasus following the Russo-Persian treaty which guaranteed the Russian

control of the Caucasus.

The Transcaucasian Railway (completed in 1870) connected the main ports of Baku (The Caspian Sea) and Batumi (the Black Sea) and opened the Caucasus to the world; goods, including rugs could have been now transported and exported worldwide.

According to Tschebull, this marks the beginning of the Renaissance of the Caucasian rug industry.

Kazaks, Shirvan, Kubas quickly caught the attention of home owners in Europe and the United States. The demand for these colorful, casual and inexpensive rugs grew steadily culminating perhaos at the turn of the 19th and the 20th cecntury.

Two decades later however it was all over.

Scholars point to three designs realated to a very old rug making tradition in the Caucasus; the so-called Eagle and Cloudband Kazaks (both actually Karabagh rugs) and Qasim Ushak rug .

The three are related to the very old Caucasian Dragon rugs feauturing motifs and dragon symbolism borrowed from Chinese mythologies.

The hugely popular Kazaks, Shirvans, and Kubas (refereed to in that period as Kabatan rugs) have no older predecessors; most artifcats in museums across Azeiberjan, Georgia and Aremania are marked as late 19th or early 20th cebtury,

Many motifs however which are dipalyed in their designs are featured in eralier textiles (e.g. scarves), ceramic tiles and other decoarive objets.