Dates appear on the oriental rugs sporadically. Unless forged to deceive buyers, they are meant to commemorate important events; weddings, births, etc.

Such dates require some historical understanding to be properly read.

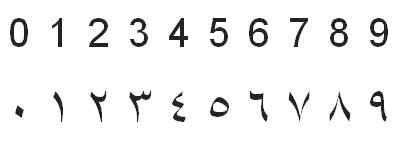

Firstly, most dates on the oriental rugs are presented in Indian numbers. This may sound strange but in truth it is the Europeans who at a point in history abandoned Roman numerals such as I, II, III, IV, V … X in favor of the Arabic ones 1,2,3,4,5 … 10.

The Arabs, on the other hand, whose trade with the Subcontinent was always of great economic importance, adopted the Indian numerals ١,٢,٣,٤,٥.١٠ which, unlike any other Arabic texts, are are read from the left to to the right.

These dates are almost always presented in Islamic (lunar) calendar and need to be converted to their Gregorian equivalent.

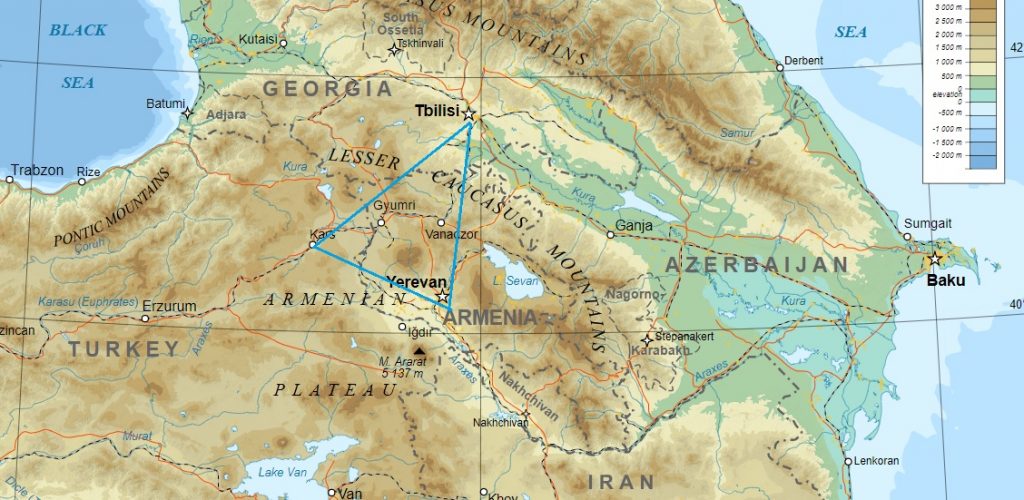

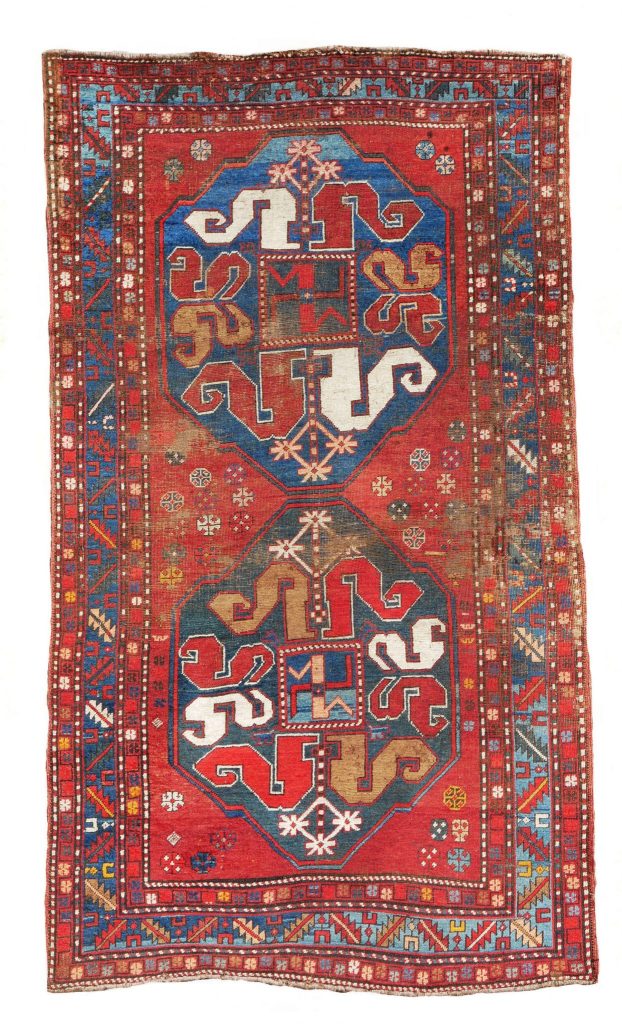

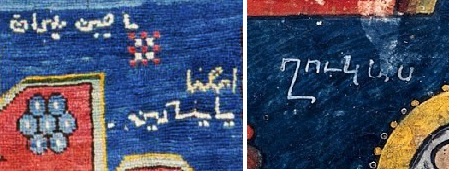

The simplest way to do it is to add 582 years to the date in question, hence, for instance, ١٣٣٣ as on the Yerevan rug in our collection meaning 1333 represents the year 1915 in Gregorian calendar.

However, in 1925 Iran (Afghanistan a few years earlier) abandoned the Lunar calendar and adopted the Solar one. Therefore, all Persian rugs bearing dates 1925 onward are much younger than the ones with dates from before 1925.

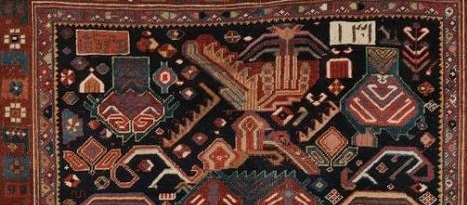

For instance, the Bijar in our collection dated ١٣٣٤ or 1334 is not just a year younger than the Yerevan one but as many as 43 years; it is in fact dated 1958 in Gregorian calendar.

When reading dates on Oriental rug dated ١٣٠٣ or 1303 (1925) onward, one ought to add 624 years to obtain the correct but approximate number.

The main challenge is to identify rugs hand-knotted and dated before or after March 1925 as that is when the calendar was re-set to accommodate 12 28-day months to the 30-day month each 12-month year.

Example: a rug dated 1333 in old lunar calendar is a 1915 antique artifact; a rug that was hand-knotted in 1334 after the 25th of March 1925 is a 1957 semi-antique or vintage rug of a much lesser collectible value.

Here is an elaborate system of accurate reading of dates on Persian (and Caucasian) rugs as recommended in Majid Amini’s Oriental Rugs Care and Repair A Van Nostrand Reinhold Book p.53

‘a. Divide the woven Persian number by 33 [The Muslim year is lunar and is [/] eleven days (or one thirty-third of a year) shorter than the Christian solar year.

b. Subtract the result of a from the vowen date

c. Add 622 (the year of Mohamed’ flight [from Mekkah to Medina] to the result of b and this will give you the Christian date.’

Example:

- 1334 : 33 = 40

- 1334 – 40 = 1294

- 1294 + 622 = AD 1916

When assessing the age of a rug, ironically, the dated rugs present the most difficulty as dates may be easily, purposely or inadvertently, misrepresented.

Most scholars and antique rug experts rely on their knowledge of dyes used in a particular artifact which offers reliable but its approximate age. The presence of a date will sometimes confirm the dye-suggested period but more often than not, it may just complicate the matter.

All in all, determining the age of an antique rug is a complex process that always implies a certain margin of error.

A.G.