Buying a rug may constitutes an opportunity to beat the inflation in many counties. In Iran, for instance, it is a common practice.

In the West, few people can be now convinced that rugs are a sound albeit long term investment.

Knowledge is the key; that little should be obvious.

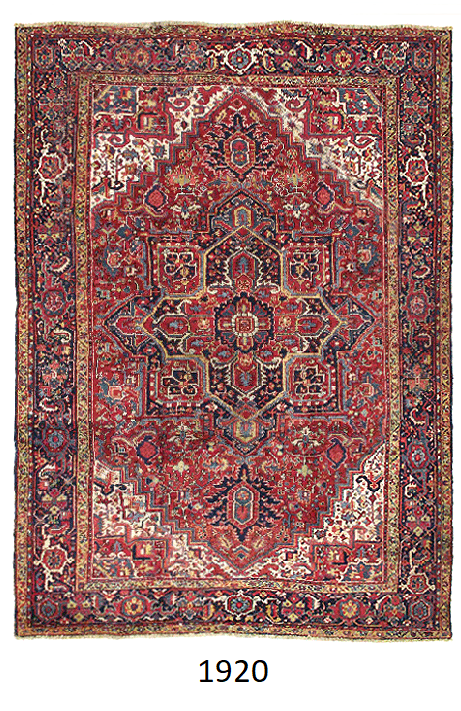

For the purpose of this research, we will focus on the US market trends stretching from the early 1900s till today with respect to Caucasian rugs, both popular and economical home décor fixtures of the period.

We will rely on the following sources: Libraries – University of Missouri and Dr. G. Griffin Lewis The Mystery of the Oriental Rug J.B Lippincott Company, published in 1914

The early 1900s in the US witnessed and an unprecedented rise in imports of Oriental carpets.

It is believed that the cost of a Caucasian rug at that time was lower than that of a machine-made one.

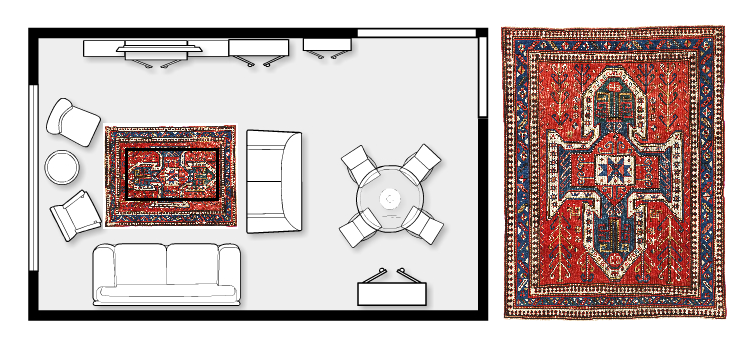

Rugs from the Caucasus were shaggy; (long nap was the term commonly used in that period) and not very elegant.

Over a period of less than a century however they began to show their true colours.

The natural process of wool corrosion (gradual flaking away of rich in iron and other metal wool ) and the contraction of the foundations brought out the beautifully harmonious tones characteristic to the antique rugs from the Caucasus and created embossed patterns of high and low pile across their surface.

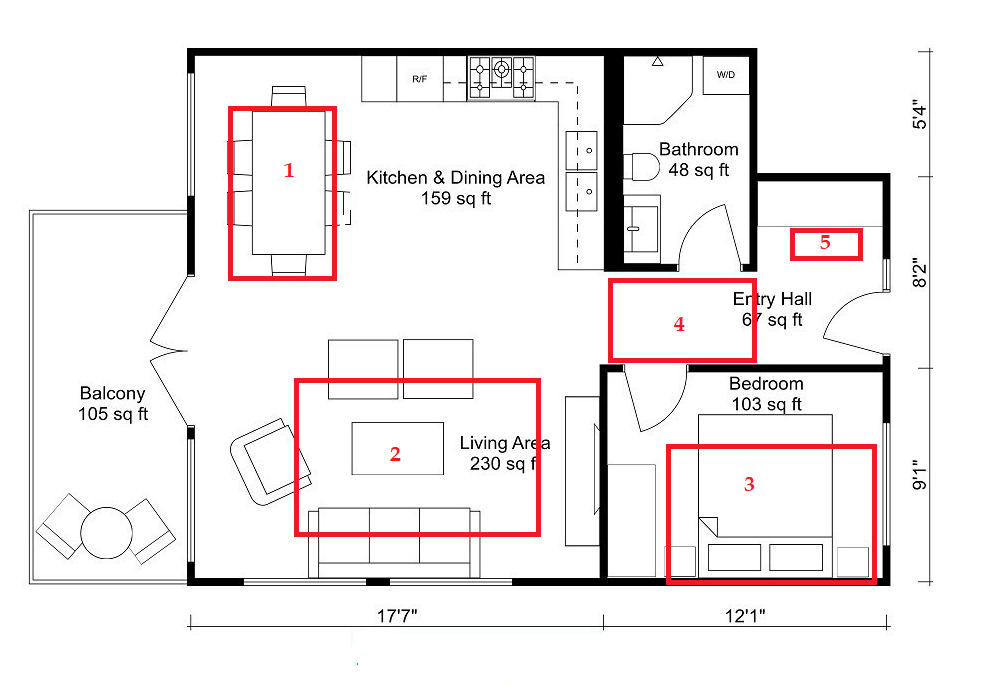

At the beginning of the 19th century, an average salary in the US was about $200 while the cost of a Caucasian rug ranged from $1.5-$3.00 per square foot. Even a family of modest means could then afford a $15-$20 rug for their home.

With hardwood floors becoming a common feature in modern home décor of the early 20th century, wool rugs became popular if not in fashion.

A $20 dollar purchase of a Caucasian rug constituted no more than a tenth (10%) of the average salary of the period in question.

A handful of these rugs survived till today; many are sold in rare rug shops and at auctions.

It is a conservative assumption that a late 19th and early 20th century Caucasian rugs can be sold/bought in the US for no less than $1500-$3000.

Thus, the average cost of an antique Kazak, Shirvan or Kuba is $2250.

Therefore, it is also a conservative assumption to suggest that an average Caucasian rug from the turn of the past century increased in value more +/- tenfold in market value approaching the cost of an average full one month salary in the US.

The number of these rugs is diminishing (at least certainly not growing); the question is whether the value of these rugs will increase at the same pace.

Hypothetically, we can assume that the cost of a Caucasian rug purchased in e.g. in New York in 1910 for $20 (a tenth of a monthly salary) may reach the value of a nearly one full annual salary in the US in 2100.

A.G.